Crisis:

1. Pathol. The point in the progress of a disease when an important development or change takes place which is decisive of recovery or death; the turning point of a disease for better or worse. 2. Astrol. Said of a conjunction of the planets which determines the issue of a disease or critical point in the course of events. 3. transf and fig. A vitally important or decisive stage in the progress of anything … now applied esp. to times of difficulty, insecurity, and suspense in politics or commerce. —Oxford English Dictionary

I. A Critic’s Progress

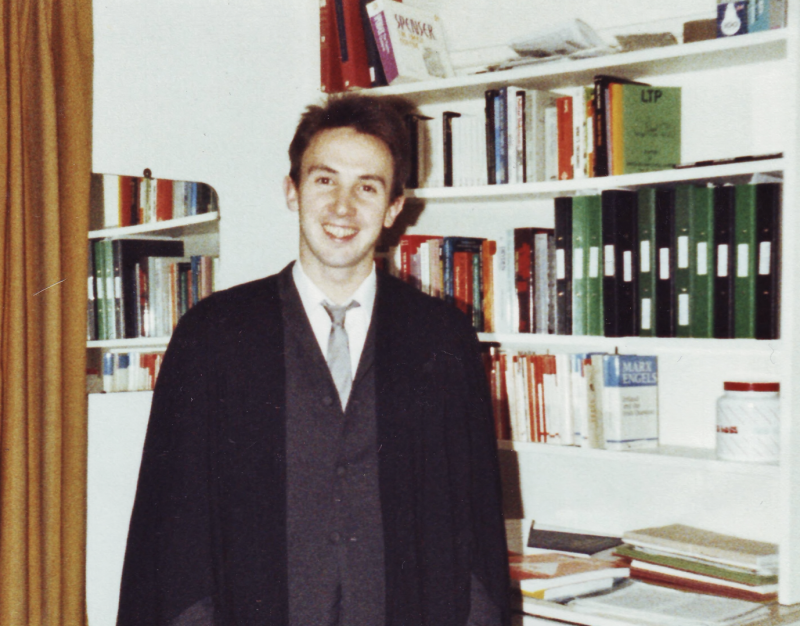

Every life has its critical turning points, its conjunctions, and its decisive stages. My journey began at a time when I had no intention of going to University. After I left school in 1978, I worked for three years in three different jobs: for the Roads Department of Strathclyde Regional Council, the Royal Bank of Scotland, and Glasgow City Libraries, respectively. These weren’t gap years; at the time I had no plan for further study, nor the qualifications to do so. My parents had never gone to university, nor had any of my six older siblings. I would be the first in my family for as many generations as I knew of. But in 1980, while working as a library assistant I sat, and passed, an additional exam in History at evening classes. This meant I could apply to university in order to get a professional qualification in Librarianship. I didn’t know it at the time, but in 1981 I set out on what became the road to the Renaissance, first as an undergraduate at the University of Strathclyde, and then as a PhD student at the University of Cambridge in the latter part of that decade.[1] The Scottish four-year degree structure entailed five courses in first year, reducing to two in second and third year, then homing in on Joint or Single Honours. My five first-year subjects at Strathclyde reflected not only my interests but also the fact that I had chosen a partly vocational degree. I remained an employee of Glasgow City Libraries when I matriculated, with a guaranteed summer job throughout the course of my studies, as well as the promise of a permanent post as an assistant librarian on graduation.

Where I came from, most of my peers had left school without qualifications and were glad of a job of any description, so white-collar work such as the library was looked on favourably. In first year, my chosen subjects, in addition to Librarianship, were Politics, Modern History, Economic History, and English. At the end of that year I did well in all subjects except Librarianship, which I failed with a mark of 38%. While I loved books and loved working in a library—I still count it as the best job I ever had—I found the course boring, and I’ve never been good at things that bore me. I managed to scrape a bare pass—50%—for the resit. When the results came out, I was summoned to the Director of Libraries’ office and given a choice. I had to either resign from the library service if I wanted to remain at university or give up on my studies altogether and come back to work in my old post as an unqualified librarian. I had to think about this. I had never wanted to be anything other than a librarian. It seemed unjust that I had passed the resit but was being treated as a failed student by my employer. This injustice marked a major turning point in my life. It ended my dream of being a librarian and set me on the road to an academic career, since I chose to stay on at Strathclyde and pursue another degree pathway. The allure of English and Politics won the day.

In my second year, alongside Renaissance Literature I studied Milton and Hobbes as part of a course in Modern Political Thought. It was a good fit. In third year, I was drawn more to the Politics options than the English ones, so I took three courses in that subject area — Political Ideologies, Nationalism, and Communist Political Systems — plus one English option, Augustans and Romantics, which left me cold. This spread of subjects in third year effectively limited me to a fourth-year prospect of Single Honours Politics or Joint Honours Politics and English, since no student who took only one English course in third year could progress to Single Honours in that subject. In terms of fourth-year options my preferred Politics course—Seventeenth-century Political Thought—wasn’t being run in 1984-5 due to a staff sabbatical. I was not drawn to the remaining courses in electoral, statistical, and behavioural politics, areas in which Strathclyde’s Politics Department would soon establish itself as a world leader. Conversely, the English modules like Literary Theory, Shakespeare, Modern Literature, and Contemporary Literature looked enticing, and for this reason in 1984 I gave up Politics for English. In doing so, I bent the rules by switching from majoring in Politics with an English minor to Single Honours English. I never looked back, finding there was much more politics in English to engage me than I had found in the study of Politics itself. Around that time, I had read Terry Eagleton’s Literary Theory (1983) and was bowled over. To my mind, its conclusion, “Political Criticism,” pulled the rug out from everything preceding it.

Eagleton declared:

The present crisis in the field of literary studies is at root a crisis in the definition of the subject itself. . . . Nobody is likely to be dismissed from an academic job for trying on a little semiotic analysis of Edmund Spenser; they are likely to be shown the door, or refused entry through it in the first place, if they question whether the ‘tradition’ from Spenser to Shakespeare and Milton is the best or only way of carving up discourse into a syllabus. It is at this point that the canon is trundled out to blast offenders out of the literary arena.[2]

In this video, I look back at Terry Eagleton’s Literary Theory. Does it remain compelling today?

Willy Maley on Terry Eagleton, “Then and Now”

Although I liked Eagleton’s polemical style and was engaged by theory and eager to question the canon, at this stage I was more interested in dismantling it from within than denouncing it. At Strathclyde there was a good balance between literary theory and Renaissance Literature, exemplified in the figure of Derek Attridge. Like Cardiff and Sussex, Strathclyde was buzzing with new ideas. Alan Durant and Nigel Fabb added linguistic interests to political ones.

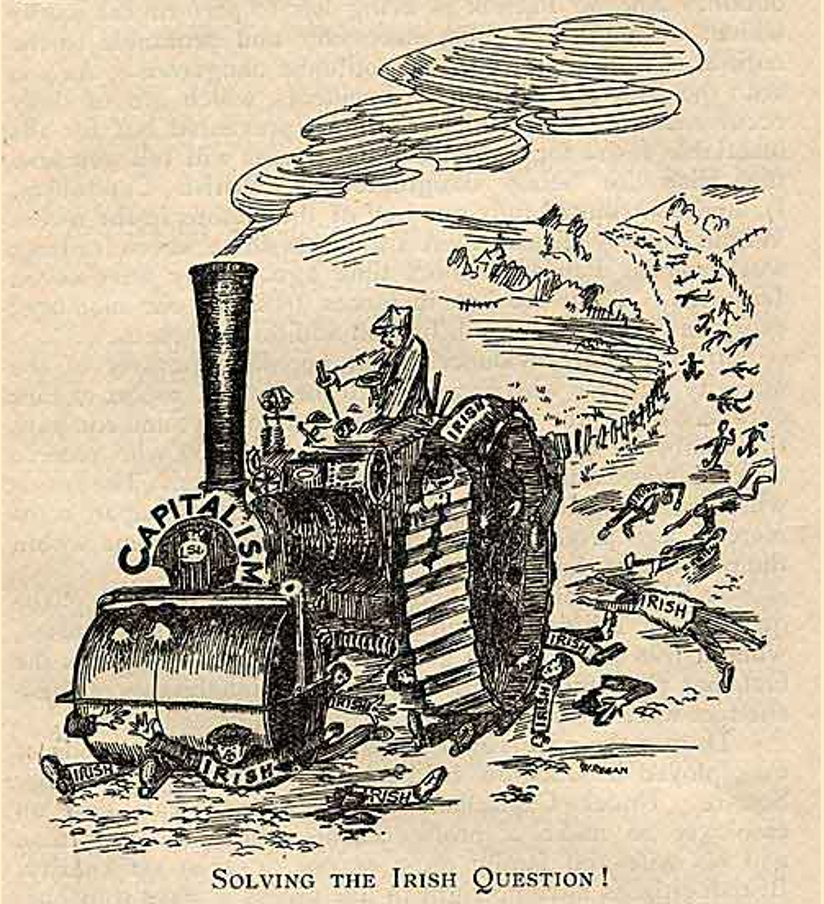

My interests in colonialism, deconstruction, and Marxism came together in the shared claims of those fields that margins determined centres. I used to joke about establishing a “Centre for Marginal Studies.” From Derrida I learned that marginal or fringe cases “always constitute the most certain and most decisive indices wherever essential conditions are to be grasped”.[3] For Marx, comparing the 1790s with the 1640s, “from a revolutionary standpoint, the Irish were too far advanced for the English King and Church mob, while . . . the English reaction in England had its roots (as in Cromwell’s time) in the subjugation of Ireland” (Marx’s emphasis).[4]

Long before archipelagic history became fashionable, I was persuaded by Marx’s argument that the English revolution failed because of the emerging British empire which cut through commonwealth and crown like an arrow: “As a matter of fact, the English republic under Cromwell met shipwreck in—Ireland.”[5] Marx recognised that class tensions were displaced onto nation and empire, even though this went against his earlier convictions:

For a long time I believed that it would be possible to overthrow the Irish regime by English working-class ascendancy. . . . Deeper study has now convinced me of the opposite. The English working class will never accomplish anything before it has got rid of Ireland. The lever must be applied in Ireland. That is why the Irish question is so important for the social movement in general.[6]

I’ve always liked those lines: “For a long time I believed,” and “Deeper study has now convinced me of the opposite.” They seem to me to be about an openness to education, research, lifelong learning, and history.

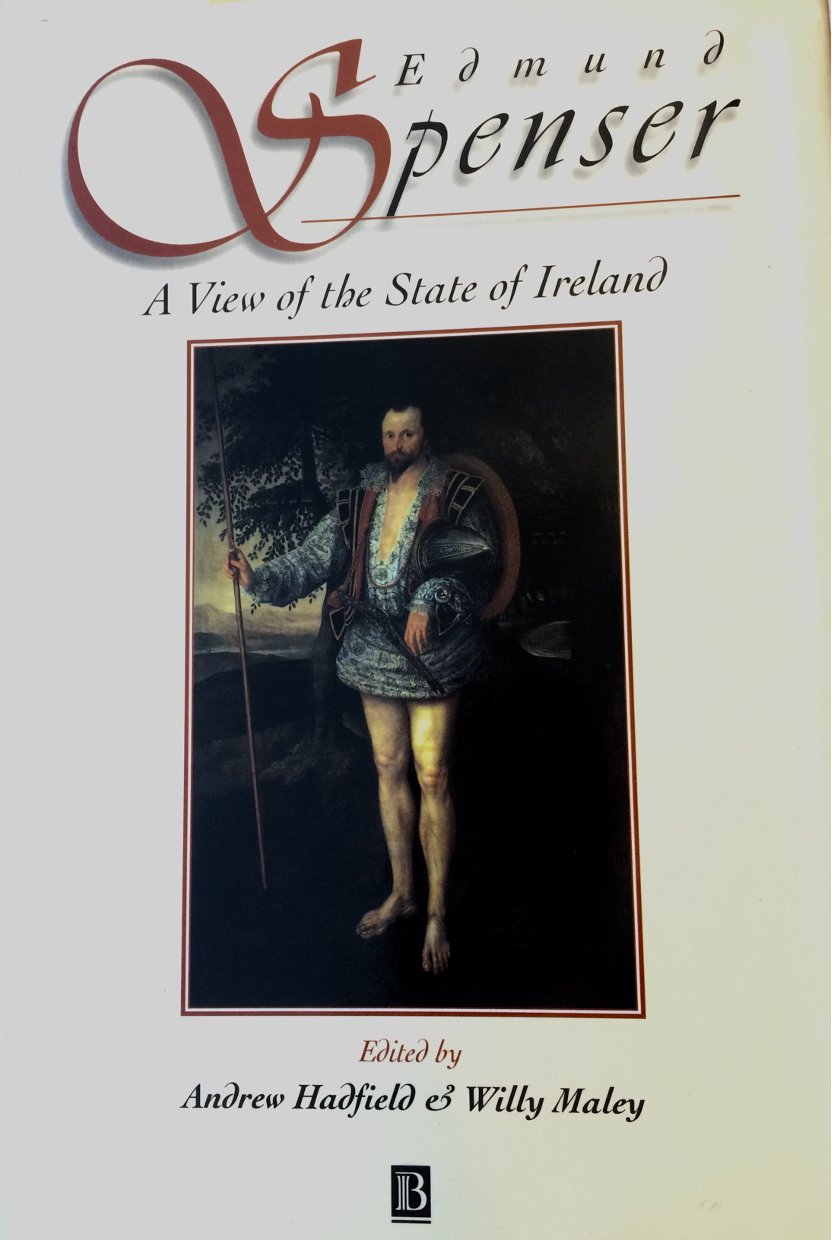

I wrote my final dissertation at Strathclyde in 1984–85 on Edmund Spenser, supervised by Colin MacCabe. Simon Adams in the History Department provided additional support and made me regret that I’d had to give up that subject in second year. As part of my research I read A View of the State of Ireland (in the Variorum edition) and had the first hankerings after a bigger project, though I still wasn’t sure what or how. I would later go on to produce an edition of Spenser’s text with Andrew Hadfield.

My enthusiasm for English paid off with a good degree. I got a distinction, thanks in part to my dissertation on Spenser. Derek Attridge suggested after graduation that I go live in a garret and write—creatively rather than critically. I didn’t know what a garret was, but it sounded too much like a garrote or a ghetto for my liking, so his second suggestion struck home: Why not apply to Cambridge or Oxford? I applied to both. A counterproposal was made by another Strathclyde professor, Colin MacCabe, who had some history with Cambridge around the so-called “structuralist controversy” of 1980-81. Colin suggested I’d thrive more at Sussex, so I also applied there and was accepted onto the new Renaissance MPhil taught by Jonathan Dollimore and Alan Sinfield, whose collection of essays, Political Shakespeare, would prove to be a crucial bridging text between my studies at Strathclyde and Cambridge.

But my dream at the time was to study with Terry Eagleton, and when I was accepted at Oxford it looked like the dream was going to come true. It died when Eagleton wrote to inform me that he didn’t work on Spenser. I hadn’t really thought about seeking out an academic adviser who had expertise in my chosen field. My instinct was to say to Eagleton: “Okay then, what do you do, and I’ll revise my proposal accordingly.” (Proposals in those days were brief working titles and statements of intent, not the overly elaborate promissory notes they have become.)

In the interim, however, I had also been accepted at Cambridge. When I made a visit there in the summer of 1985 and met with my prospective supervisor Lisa Jardine at Jesus College, it was clear that she was extremely well qualified to supervise me. In the end I opted for Cambridge and embarked on a PhD thesis entitled “Marx and Spenser: Elizabeth and the Problem of Imperial Power,” funded by the Scottish Education Department as it was then known. My starting point was that Spenser was a poet in crisis, and this crisis had something to do with Ireland and history and language.

Lisa Jardine was a scholarly Marxist feminist from an interdisciplinary background. She taught me footnotes and a slower way of working than my undergraduate verbal energy had prepared me for. Lisa provided a different model of intellectual engagement, quite distinct from Eagleton’s. I would later mark out my distance from him, but I was still at the time of my doctoral research a devout Eagletonian.[7] When Eagleton’s book on Shakespeare appeared from Blackwell as part of the Rereading Literature series in 1986, I decided that I would aim to contribute the Spenser volume to that series. That plan never worked out, partly because Eagleton as series editor doubted that a Spenser volume would be commercially viable at the time.[8] In 1986, at the end of my second year in Cambridge, Ciaran Brady’s landmark essay, “Spenser’s Irish Crisis: Humanism and Experience in the 1590s,” appeared in Past and Present, triggering a lively debate with two other Irish historians, Nicholas Canny and Brendan Bradshaw.

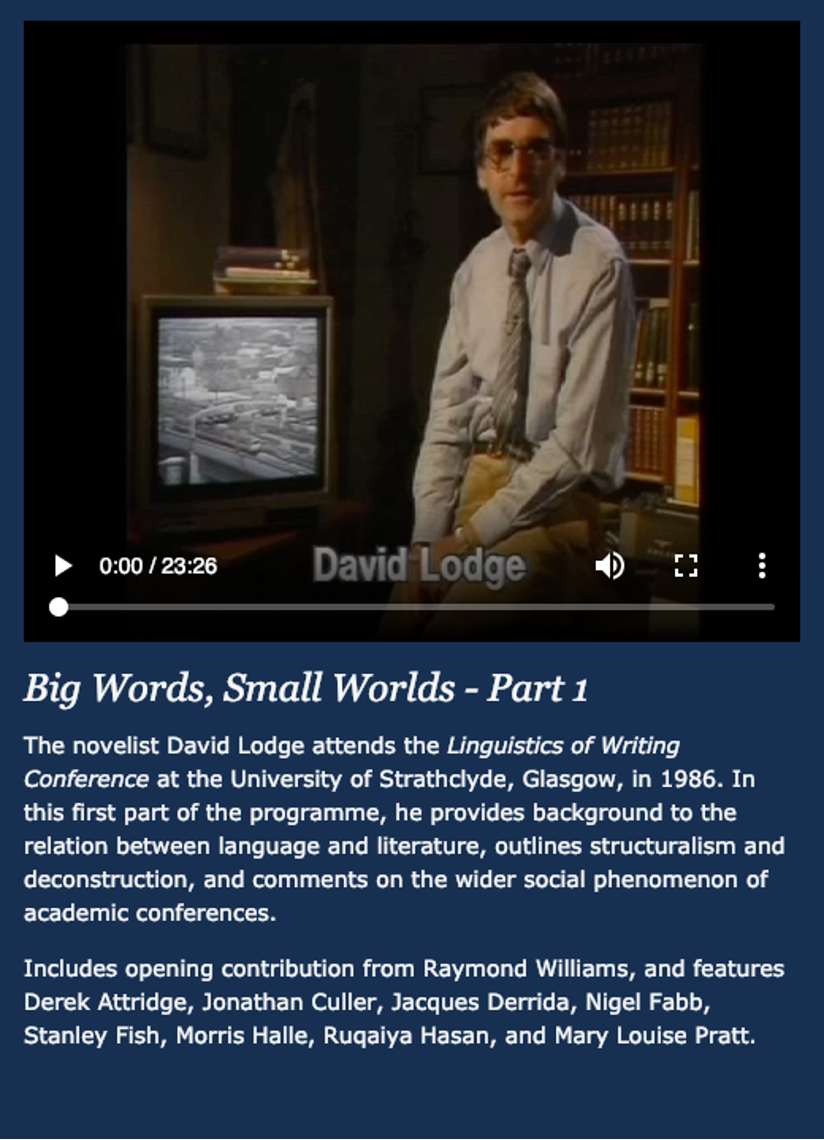

In the summer of 1986 I was back at Strathclyde as a conference coordinator (postgraduate helper) at The Linguistics of Writing conference organized by Derek Attridge, Alan Durant, Nigel Fabb, and Colin MacCabe.

This was a watershed conference, as important in its own way as the Johns Hopkins structuralism/poststructuralism conference of 1966. The event was filmed and shown on Channel 4 in the UK as a pioneering postmodern documentary, presented by David Lodge.

Raymond Williams, the renowned Welsh Marxist, who was a Fellow of Jesus College Cambridge at the time was a key speaker from my perspective as a major thinker on the Left. Other leading lights of the Left—Terry Eagleton, Fredric Jameson, and Edward Said—were all scheduled to appear but for one reason or another failed to materialize. Those no-shows cast a shadow over proceedings.

Jacques Derrida did appear, and he stole the show.

It was my first major conference, and an intervention of mine, in which I lamented the absence of the critical Left from proceedings, happened to make it into the documentary. Although I was lamenting the absence of the big guns of the Left, it was the beginning of a love affair with deconstruction. By the following year, I was reading everything by Derrida that I could lay my monolingual hands on. I told Derek Attridge, arch-Derridean, about my newfound interest, and he was worried that it would distract me from my PhD on Spenser. He advised that it should be a shadow obsession and not get in the way. I remember telling him I would adopt Derrida’s idea of Plato’s pharmacy as Spenser’s dispensary, but that idea never quite took off and I remained broadly historicist in my approach.

The polemical style required for writing under pressure came easily to me, but the stately pace of scholarship was a different matter. I found the middle years of my PhD, 1986–87, very difficult. The loneliness of the long-distance researcher is part of the PhD experience, but at Cambridge my isolation felt so intense, in particular my sense of social alienation, that I began to doubt I would ever reach the end of the road. I kept hitting my head against the class ceiling, constantly being questioned as to whether I belonged at Cambridge, being taken for a non-student because of my working-class accent. There were financial pressures, too. Both my parents were pensioners by this time, and my funding body, the Scottish Education Department, was beginning to ask questions as to why it was paying a college fee as well as a University fee for its Oxbridge award holders. All Scottish students were summoned one day to be told that they were no longer members of the College, only for this to be rescinded within the week. This crisis in funding was presumably due to some sort of institutional anomaly, but it left me feeling even more insecure.

Around that time, I had a lesson in career planning that helped me through this difficult stage. In 1987, I was in Cambridge University Library when I was paged to go to the phone at the main desk.

_bollards_in_front_of_Cambridge_University_Library.jpg)

It was a former tutor who wanted to pay me £100 to carry out a search of the library for a list of the items he had published—mainly reviews and short essays — over the previous twenty years, but hadn’t kept track of. Some were in the Times Literary Supplement, others in more obscure places. I did this task in one long day, working from a very rough list of half-remembered locations. I came across other material by other academics—early reviews by Terry Eagleton and others, including Lisa Jardine, my own PhD supervisor. It was an education for at least two reasons. First, because it provided me with a glimpse into something that nobody had ever told me about: an academic apprenticeship. I realised that many academics seemed to have started out by writing reviews and short pieces. Second, because I saw that long after the initial thrill of publishing was gone, it was perfectly possible for prolific academics to lose track of what they had done. I learned that it was essential not to rely on anyone else to record all of the things that you might do in connection with teaching, research, and writing. It was too late if you waited for that moment to come when you were asked for information that you no longer had to hand. Academics always do much more work than they would imagine including, and it is essential to start as you mean to continue and keep a full record of everything you do. In my next supervision with Lisa Jardine, I mentioned this request to research another academic’s list of publications, and she told me that when her CV got to twenty pages, she started letting things that she wasn’t especially keen on fall off the edge. My CV was a few lines long at the time, so the prospect of a twenty-page CV was daunting.

Cambridge was an education in many other ways than an immersion in early modern culture. For one thing, I saw in starker terms than at Strathclyde the gender imbalance in staffing. Visiting the Senior Common Room at Jesus College as Lisa’s guest, I saw the only other woman present serving tea. I also learned for the first time the phrase “it’s not my period,” used by staff and students alike to indicate that their expertise lay in a different historical era from the one under discussion. Cambridge was not my period insofar as I felt out of place and out of time. But here I would want to distance myself from a class critique of Cambridge—or a social critique of Oxbridge—that overlooks the extent to which other institutions, including my Scottish alma mater, the University of Strathclyde, are riddled with similar inequalities, albeit less glaringly. Class remains an issue that needs to be addressed alongside other differences and exclusions.

I had my first viva—oral examination—for my PhD thesis at Cambridge University in April 1989. I say first viva because I was one of that small unhappy band who are “referred.” Although I felt I had a good viva and actually enjoyed engaging in heated debate over three hours in defense of my thesis, I found out via a phone call from my supervisor the next day that both examiners recommended I be referred. It was not easy explaining to family and friends not versed in these matters that my doctorate had been put on hold. It was a deeply dispiriting experience, especially because I was in the process of applying for jobs, and it ranked as a failure of sorts. It was only later that I discovered my own supervisor, one of the most brilliant Renaissance critics of her generation, was also “referred,” and one of my academic referees had gone through the same experience, so I was not alone.

I worked hard over the summer and resubmitted in September 1989. Five months later, in February 1990, I had my second viva, from which there is no return. To fail one viva is carelessness, to fail two is fatal. How strange to think that a job in Glasgow City Libraries was all I had aimed for a decade earlier. At the end of the meeting, as I was leaving the room, none the wiser as to my progress, the external examiner asked: “Aren’t we going to tell him?” For a fleeting moment, I was a rabbit caught in the headlights of a juggernaut. Then, somewhat reluctantly, I heard the internal examiner mutter: “Yes, I suppose we’d better.” It was official. I had got a result. I was a doctor, qualified to write literary prescriptions with clinical precision and to perform surgical operations on ailing texts. During the interval between the first and second viva, I had, as is the way of things, stored up a modicum of resentment against my original examiners, but to my surprise and relief this ill will evaporated after I was awarded my degree. That particular crisis was over.

The heady joy was short-lived, since what followed was four years of unemployment or underemployment. This, it turns out, is not unusual. The wilderness years can last between three and five years on average for post-doctoral academics. There are luckier ones, of course, but as someone who had worked full-time for three years after leaving school this was a taxing period. At the time of my appointment at the University of Glasgow in 1994 I read in a higher education trade union bulletin that those academics in the UK who successfully secure permanent posts do so on average at the age of 32. I was 33. At the time I didn’t know about this gap between completing a PhD and getting a permanent post, so I assumed my CV must be the problem. Of course, in part it was. After failing to be shortlisted for a job in Dundee in the early 1990s, I learned that the lectureship had gone to someone in their mid-thirties who had two books to their name. That put things in perspective. I happened to mention my lack of success in securing interviews to Tom Furniss at Strathclyde, where I was teaching part-time, and he offered to look at my CV. He pointed out that I should be recording things like seminar and conference papers, teaching experience, and minor publications like newspaper journalism, which I was starting to accumulate. One radically overhauled CV later, and I was on the first rung of the ladder with two temporary posts in London, from where I applied for a permanent position at Glasgow.

II. The Time Is Out of Joint

Apart from my own personal crises of class, confidence, and conscience, two historical crises occupied me at Cambridge, and still do. Both were billed as crises and were log-jams in terms of critical attention. The first was the crisis of the 1590s, the second the crisis of the 1640s. The early modern period, I discovered, was characterized by crisis, whether social, political, and educational, or bound up with monarchical succession or exclusion.[9] Eric Hobsbawm’s 1954 intervention underpinned this post-war preoccupation with a crisis that occurred three centuries earlier.[10] Hobsbawm’s contention was that “The European economy passed through a ‘general crisis’ during the 17th century, the last phase of the general transition from a feudal to a capitalist economy.”[11] Hobsbawm did not, like Marx, suggest that Empire limited social change in the period. Rather he saw Empire as itself in crisis:

It is also clear that the expansion of Europe passed through a crisis. Though the foundations of the fabulous colonial system of the 18th century were laid mainly after 1650, earlier there may actually have been some contraction of European influence except in the hinterlands of Siberia and America. The Spanish and Portuguese empires of course contracted and changed character. But it is also worth noting that the Dutch did not maintain the remarkable rate of expansion of 1600 to 1640 and their Empire actually shrank in the next 30 years. The collapse of the Dutch West India company after the 1640s, and the simultaneous winding-up of the English Africa Company and the Dutch West India Company in the early 1670s may be mentioned in passing.[12]

Hobsbawm goes on to say: “It will be generally agreed that the 17th century was one of social revolt both in Western and Eastern Europe.”[13] Again, Hobsbawm does not, like Marx, tie Empire to the displacement and suppression of social revolt. By downplaying Empire and playing up the English Revolution—the one Marx said was shipwrecked on Ireland—Hobsbawm arrives at a perspective in which

the economic history of the modern world from the middle of the 17th century hinges on that of England, which began the period of crisis—say in the 1610s—as a dynamic, but a minor power, and ended it in the 1710s as one of the world’s masters. The English Revolution, with all its far-reaching results, is therefore in a real sense the most decisive product of the 17th century crisis.[14]

One of the most acute analysts of the crisis mode in critical discourse was Jacques Derrida, who responded at length and variously to Francis Fukuyama’s “The End of History,” published as an essay in 1989 and expanded into a book in 1992.[15]

In Specters of Marx, Derrida argued that the capitalist crisis was structural and longstanding, and that an apocalyptic tone was both overdue and premature:

The time is out of joint. The world is going badly. It is worn but its wear no longer counts. Old age or youth—one no longer counts in that way. The world has more than one age. We lack the measure of the measure. We no longer realize the wear, we no longer take account of it as of a single age in the progress of history. Neither maturation, nor crisis, nor even agony. Something else. What is happening is happening to age itself, it strikes a blow at the teleological order of history. What is coming, in which the untimely appears, is happening to time but it does not happen in time. Contretemps. The time is out of joint.[16]

“The time is out of joint” is a useful expression to apply to crisis talk, since it sets in play a temporal dissonance that makes notions of development and progress problematic. The crisis is always already happening.

In this video, I address the questions: Is literary criticism in crisis? And is political criticism in crisis?

And as I read Derrida and Marx, I was also struck by the long view those thinkers took of “crisis” as a recurrent feature of language, culture, and economy. Academic time passes slowly and is always out of joint. Loitering with intent around the 1590s and 1640s, as I often do, puts things in perspective and affords a long view of the crisis in politics and education. A comment on the Nine Years War in Ireland (1594–1603) by Brian Outhwaite, an historian whose work spanned four centuries, made me see that it was not ahistorical or transhistorical to make connections across periods: ‘This, as far as the professional soldiers were concerned, was the most hated war of their era: England’s Vietnam.”[17]

Years later, I would see a reader’s report on a collection of essays on early modern Ireland that condemned a contributor for drawing an analogy between the Munster Famine of the 1580s and the Hunger Strikes of the 1980s. Crises had to be kept in their boxes—cross-period comparisons must not be made. Presentism has its problems, but it seems to me that refusing to recognize the links between past and present or the longstanding nature of crises is equally problematic.[18]

Tom Paulin’s Ireland and the English Crisis (1985) had already hinted at the fact that the crisis in question was a colonial one, and Paulin anticipated the historiographical turn towards the so-called “British Problem,” a paradigm that had the virtue of making a problem of the British imperial monarchy rather than pondering an “Irish Question.”[19] When I read Terry Hawkes’s That Shakespeherian Rag in 1986, I was struck by his conclusion. For Hawkes, “English”—nation and subject—cohered around questions of colonialism and elitism, and he alluded to

a complex relationship between the academic subject of English and the culture, identity and purpose which that subject was designed to serve: ‘Englishness’. The one sustains, and even helps to create the other. And yet … a series of continuing confrontations has brought just this matter of ‘Englishness’ into question. Issues raised by events in Ireland and Ulster, the retreat from colonialism followed by immigration from former colonies, the rise of Welsh and Scottish nationalism … have all to some degree brought into focus the matter of the definition, limits and specific character of ‘Englishness’…. Current talk of a ‘crisis’ in English neglects that history. There is no crisis in English. There was and is a crisis which created English and of which it remains a distinctive manifestation: a child of Empire’s decline, we might say, by America out of Russia.[20]

The political crisis that impacts on the humanities, I would argue, including English studies and early modern studies, is a constant crisis.

Naomi Klein’s groundbreaking book, The Shock Doctrine, tracks the rise of “disaster capitalism,” which has its roots in the exploitation of crisis as a means of encroaching on the public sphere and civil liberties:

For more than three decades, [Milton] Friedman and his powerful followers had been perfecting this very strategy: waiting for a major crisis, then selling off pieces of the state to private players while citizens were still reeling from the shock, then quickly making the ‘reforms’ permanent.[21]

It’s not simply that one person’s crisis is another’s opportunity. Rather, one person’s crisis can be another’s opportunism. Klein’s timeline could be pushed back further, all the way to Milton. In the middle of the seventeenth century, a “constitutional crisis” created the opportunity for conquest and colonization out of the threat of radical change, as first a colonial republic and then an imperial monarchy crushed popular demands for an extension of the franchise and freedoms.[22] “The Shock Doctrine” is, of course, a strategy of the Right to instill fear and panic, but I want to suggest that it has its radical counterpart as an opening, or an opportunity used by the Left in the name of taking advantage of yet another capitalist crisis.[23] Crisis itself is template rather than trigger. I am aware that this can appear a reactionary stance that denies change—constancy triumphing over mutability—but am equally alert to the risk of being blind to precedent and the uses of panic.[24] I believe that deeper study of the early modern period can provide us with insights into the present, but those insights may be bound up with a feeling of déjà vu, since rather than seeing capitalism “in” crisis, we may see that capitalism “is” crisis, and that the wars and struggles and debates to which it gives rise are part of a process rather than a series of disconnected events. Crisis is also a critical trope, and one that can conceal rather than reveal the workings of history. Crisis talk is tough talk, but it may ultimately distract us from the tougher task of reading and teaching.[25] The crises, like the poor, are with us always—unless of course we can find a way of changing “always” into history.

As an English sub-panel member for REF2014—the UK Research Assessment Exercise—I read a rich range of material, from medical humanities to the history of the book. I am struck by the current diversity of the discipline when I recall the printed list of PhD topics of my Cambridge contemporaries that I picked up from my pigeonhole in 1985. The field of English has been transformed, and the shape it has taken is quite different from that mapped out by Terry Eagleton in his conclusion to Literary Theory in 1983 when “the end of English” (the title of a 1987 essay by Eagleton) seemed imminent and an apocalyptic tone was the order of the day.[26] Admittedly, crisis talk serves a purpose, even if the crisis that is the focus of discussion is manufactured by the discussants. As Jan de Vries observes, commenting on the short-lived historiographical fashion for a crisis of the seventeenth century, “the efforts to develop the concept had not been altogether in vain—they had served the worthy cause of advancing comparative history—but they had not led to broad agreement about the definition, scope, or even existence of a crisis.”[27] My own feeling, though, is that if crisis talk is not to prove to be careless talk, then we need to focus on the longstanding causes of crises. The problem of imperial power, I think, is a good place to begin, especially from the standpoint of the current Elizabethan imperial monarchy from within which I write and teach. Elizabeth I, I like to remind people, ruled over England, Ireland and Wales, but never Scotland. England’s Elizabeth II is Scotland’s Elizabeth I. The time—now, always—is out of joint.

III. Early Modern Studies Today

In this longer video, I elaborate on where we have been in early modern criticism, where we are now, and where we might be going. My topics include the technology-driven revolution in early modern literary studies, the “New British History,” new directions in Irish studies, the future of “archipelagic” literary history, and more.

I would like to thank David Baker and Pat Palmer for the original invitation and Paddy Fumerton and Andrew Griffin for judicious advice. Thanks to Dini Power for filming the video sections of this essay in my office at the University of Glasgow on 23 July 2018, and for selected images from her private collection. Thanks finally to Arleane Ralph for judicious pruning and for asking good questions.

[1] I expand on this intellectual autobiography in a chapter entitled “Uni and Me,” in Crrritic! Sighs, Cries, Lies, Insults, Outbursts, Hoaxes, Disasters, Letters of Resignation, and Various Other Noises Off in These the First and Last Days of Literary Criticism, Not to Mention the University, Critical Interventions series, ed. John Schad and Oliver Tearle (Brighton: Sussex Academic Press, 2011), 206–20.

[1] I expand on this intellectual autobiography in a chapter entitled “Uni and Me,” in Crrritic! Sighs, Cries, Lies, Insults, Outbursts, Hoaxes, Disasters, Letters of Resignation, and Various Other Noises Off in These the First and Last Days of Literary Criticism, Not to Mention the University, Critical Interventions series, ed. John Schad and Oliver Tearle (Brighton: Sussex Academic Press, 2011), 206–20.

[1] I expand on this intellectual autobiography in a chapter entitled “Uni and Me,” in Crrritic! Sighs, Cries, Lies, Insults, Outbursts, Hoaxes, Disasters, Letters of Resignation, and Various Other Noises Off in These the First and Last Days of Literary Criticism, Not to Mention the University, Critical Interventions series, ed. John Schad and Oliver Tearle (Brighton: Sussex Academic Press, 2011), 206–20.

[1] I expand on this intellectual autobiography in a chapter entitled “Uni and Me,” in Crrritic! Sighs, Cries, Lies, Insults, Outbursts, Hoaxes, Disasters, Letters of Resignation, and Various Other Noises Off in These the First and Last Days of Literary Criticism, Not to Mention the University, Critical Interventions series, ed. John Schad and Oliver Tearle (Brighton: Sussex Academic Press, 2011), 206–20.

[1] I expand on this intellectual autobiography in a chapter entitled “Uni and Me,” in Crrritic! Sighs, Cries, Lies, Insults, Outbursts, Hoaxes, Disasters, Letters of Resignation, and Various Other Noises Off in These the First and Last Days of Literary Criticism, Not to Mention the University, Critical Interventions series, ed. John Schad and Oliver Tearle (Brighton: Sussex Academic Press, 2011), 206–20.

[1] I expand on this intellectual autobiography in a chapter entitled “Uni and Me,” in Crrritic! Sighs, Cries, Lies, Insults, Outbursts, Hoaxes, Disasters, Letters of Resignation, and Various Other Noises Off in These the First and Last Days of Literary Criticism, Not to Mention the University, Critical Interventions series, ed. John Schad and Oliver Tearle (Brighton: Sussex Academic Press, 2011), 206–20.

[1] I expand on this intellectual autobiography in a chapter entitled “Uni and Me,” in Crrritic! Sighs, Cries, Lies, Insults, Outbursts, Hoaxes, Disasters, Letters of Resignation, and Various Other Noises Off in These the First and Last Days of Literary Criticism, Not to Mention the University, Critical Interventions series, ed. John Schad and Oliver Tearle (Brighton: Sussex Academic Press, 2011), 206–20.

[1] I expand on this intellectual autobiography in a chapter entitled “Uni and Me,” in Crrritic! Sighs, Cries, Lies, Insults, Outbursts, Hoaxes, Disasters, Letters of Resignation, and Various Other Noises Off in These the First and Last Days of Literary Criticism, Not to Mention the University, Critical Interventions series, ed. John Schad and Oliver Tearle (Brighton: Sussex Academic Press, 2011), 206–20.

[1] I expand on this intellectual autobiography in a chapter entitled “Uni and Me,” in Crrritic! Sighs, Cries, Lies, Insults, Outbursts, Hoaxes, Disasters, Letters of Resignation, and Various Other Noises Off in These the First and Last Days of Literary Criticism, Not to Mention the University, Critical Interventions series, ed. John Schad and Oliver Tearle (Brighton: Sussex Academic Press, 2011), 206–20.

[1] I expand on this intellectual autobiography in a chapter entitled “Uni and Me,” in Crrritic! Sighs, Cries, Lies, Insults, Outbursts, Hoaxes, Disasters, Letters of Resignation, and Various Other Noises Off in These the First and Last Days of Literary Criticism, Not to Mention the University, Critical Interventions series, ed. John Schad and Oliver Tearle (Brighton: Sussex Academic Press, 2011), 206–20.

[1] I expand on this intellectual autobiography in a chapter entitled “Uni and Me,” in Crrritic! Sighs, Cries, Lies, Insults, Outbursts, Hoaxes, Disasters, Letters of Resignation, and Various Other Noises Off in These the First and Last Days of Literary Criticism, Not to Mention the University, Critical Interventions series, ed. John Schad and Oliver Tearle (Brighton: Sussex Academic Press, 2011), 206–20.

[1] I expand on this intellectual autobiography in a chapter entitled “Uni and Me,” in Crrritic! Sighs, Cries, Lies, Insults, Outbursts, Hoaxes, Disasters, Letters of Resignation, and Various Other Noises Off in These the First and Last Days of Literary Criticism, Not to Mention the University, Critical Interventions series, ed. John Schad and Oliver Tearle (Brighton: Sussex Academic Press, 2011), 206–20.

[1] I expand on this intellectual autobiography in a chapter entitled “Uni and Me,” in Crrritic! Sighs, Cries, Lies, Insults, Outbursts, Hoaxes, Disasters, Letters of Resignation, and Various Other Noises Off in These the First and Last Days of Literary Criticism, Not to Mention the University, Critical Interventions series, ed. John Schad and Oliver Tearle (Brighton: Sussex Academic Press, 2011), 206–20.

[1] I expand on this intellectual autobiography in a chapter entitled “Uni and Me,” in Crrritic! Sighs, Cries, Lies, Insults, Outbursts, Hoaxes, Disasters, Letters of Resignation, and Various Other Noises Off in These the First and Last Days of Literary Criticism, Not to Mention the University, Critical Interventions series, ed. John Schad and Oliver Tearle (Brighton: Sussex Academic Press, 2011), 206–20.

[1] I expand on this intellectual autobiography in a chapter entitled “Uni and Me,” in Crrritic! Sighs, Cries, Lies, Insults, Outbursts, Hoaxes, Disasters, Letters of Resignation, and Various Other Noises Off in These the First and Last Days of Literary Criticism, Not to Mention the University, Critical Interventions series, ed. John Schad and Oliver Tearle (Brighton: Sussex Academic Press, 2011), 206–20.

[1] I expand on this intellectual autobiography in a chapter entitled “Uni and Me,” in Crrritic! Sighs, Cries, Lies, Insults, Outbursts, Hoaxes, Disasters, Letters of Resignation, and Various Other Noises Off in These the First and Last Days of Literary Criticism, Not to Mention the University, Critical Interventions series, ed. John Schad and Oliver Tearle (Brighton: Sussex Academic Press, 2011), 206–20.

[1] I expand on this intellectual autobiography in a chapter entitled “Uni and Me,” in Crrritic! Sighs, Cries, Lies, Insults, Outbursts, Hoaxes, Disasters, Letters of Resignation, and Various Other Noises Off in These the First and Last Days of Literary Criticism, Not to Mention the University, Critical Interventions series, ed. John Schad and Oliver Tearle (Brighton: Sussex Academic Press, 2011), 206–20.

[1] I expand on this intellectual autobiography in a chapter entitled “Uni and Me,” in Crrritic! Sighs, Cries, Lies, Insults, Outbursts, Hoaxes, Disasters, Letters of Resignation, and Various Other Noises Off in These the First and Last Days of Literary Criticism, Not to Mention the University, Critical Interventions series, ed. John Schad and Oliver Tearle (Brighton: Sussex Academic Press, 2011), 206–20.

[1] I expand on this intellectual autobiography in a chapter entitled “Uni and Me,” in Crrritic! Sighs, Cries, Lies, Insults, Outbursts, Hoaxes, Disasters, Letters of Resignation, and Various Other Noises Off in These the First and Last Days of Literary Criticism, Not to Mention the University, Critical Interventions series, ed. John Schad and Oliver Tearle (Brighton: Sussex Academic Press, 2011), 206–20.

[1] I expand on this intellectual autobiography in a chapter entitled “Uni and Me,” in Crrritic! Sighs, Cries, Lies, Insults, Outbursts, Hoaxes, Disasters, Letters of Resignation, and Various Other Noises Off in These the First and Last Days of Literary Criticism, Not to Mention the University, Critical Interventions series, ed. John Schad and Oliver Tearle (Brighton: Sussex Academic Press, 2011), 206–20.

[1] I expand on this intellectual autobiography in a chapter entitled “Uni and Me,” in Crrritic! Sighs, Cries, Lies, Insults, Outbursts, Hoaxes, Disasters, Letters of Resignation, and Various Other Noises Off in These the First and Last Days of Literary Criticism, Not to Mention the University, Critical Interventions series, ed. John Schad and Oliver Tearle (Brighton: Sussex Academic Press, 2011), 206–20.

[1] I expand on this intellectual autobiography in a chapter entitled “Uni and Me,” in Crrritic! Sighs, Cries, Lies, Insults, Outbursts, Hoaxes, Disasters, Letters of Resignation, and Various Other Noises Off in These the First and Last Days of Literary Criticism, Not to Mention the University, Critical Interventions series, ed. John Schad and Oliver Tearle (Brighton: Sussex Academic Press, 2011), 206–20.

[1] I expand on this intellectual autobiography in a chapter entitled “Uni and Me,” in Crrritic! Sighs, Cries, Lies, Insults, Outbursts, Hoaxes, Disasters, Letters of Resignation, and Various Other Noises Off in These the First and Last Days of Literary Criticism, Not to Mention the University, Critical Interventions series, ed. John Schad and Oliver Tearle (Brighton: Sussex Academic Press, 2011), 206–20.

[1] I expand on this intellectual autobiography in a chapter entitled “Uni and Me,” in Crrritic! Sighs, Cries, Lies, Insults, Outbursts, Hoaxes, Disasters, Letters of Resignation, and Various Other Noises Off in These the First and Last Days of Literary Criticism, Not to Mention the University, Critical Interventions series, ed. John Schad and Oliver Tearle (Brighton: Sussex Academic Press, 2011), 206–20.

[1] I expand on this intellectual autobiography in a chapter entitled “Uni and Me,” in Crrritic! Sighs, Cries, Lies, Insults, Outbursts, Hoaxes, Disasters, Letters of Resignation, and Various Other Noises Off in These the First and Last Days of Literary Criticism, Not to Mention the University, Critical Interventions series, ed. John Schad and Oliver Tearle (Brighton: Sussex Academic Press, 2011), 206–20.

[1] I expand on this intellectual autobiography in a chapter entitled “Uni and Me,” in Crrritic! Sighs, Cries, Lies, Insults, Outbursts, Hoaxes, Disasters, Letters of Resignation, and Various Other Noises Off in These the First and Last Days of Literary Criticism, Not to Mention the University, Critical Interventions series, ed. John Schad and Oliver Tearle (Brighton: Sussex Academic Press, 2011), 206–20.

[1] I expand on this intellectual autobiography in a chapter entitled “Uni and Me,” in Crrritic! Sighs, Cries, Lies, Insults, Outbursts, Hoaxes, Disasters, Letters of Resignation, and Various Other Noises Off in These the First and Last Days of Literary Criticism, Not to Mention the University, Critical Interventions series, ed. John Schad and Oliver Tearle (Brighton: Sussex Academic Press, 2011), 206–20.