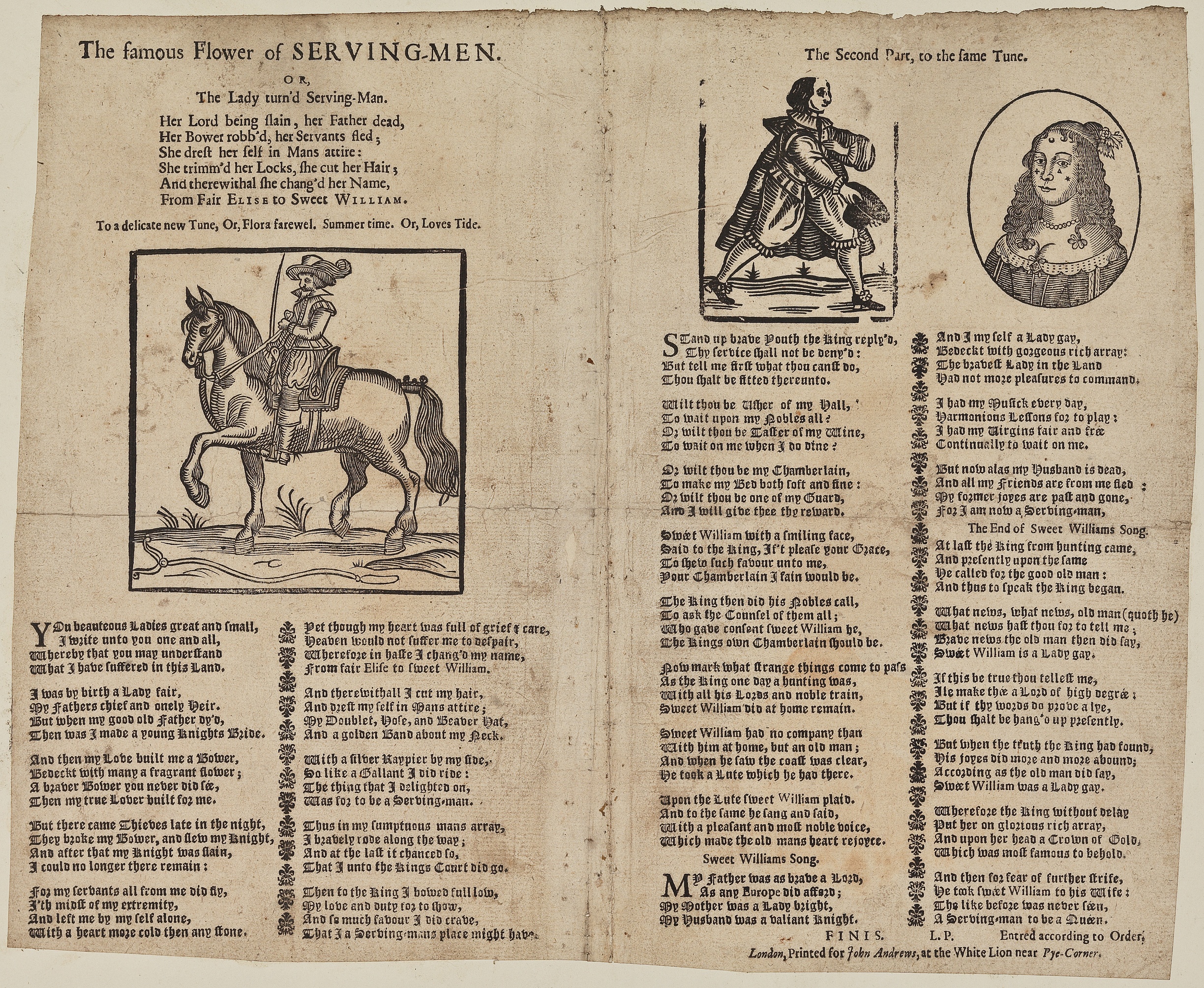

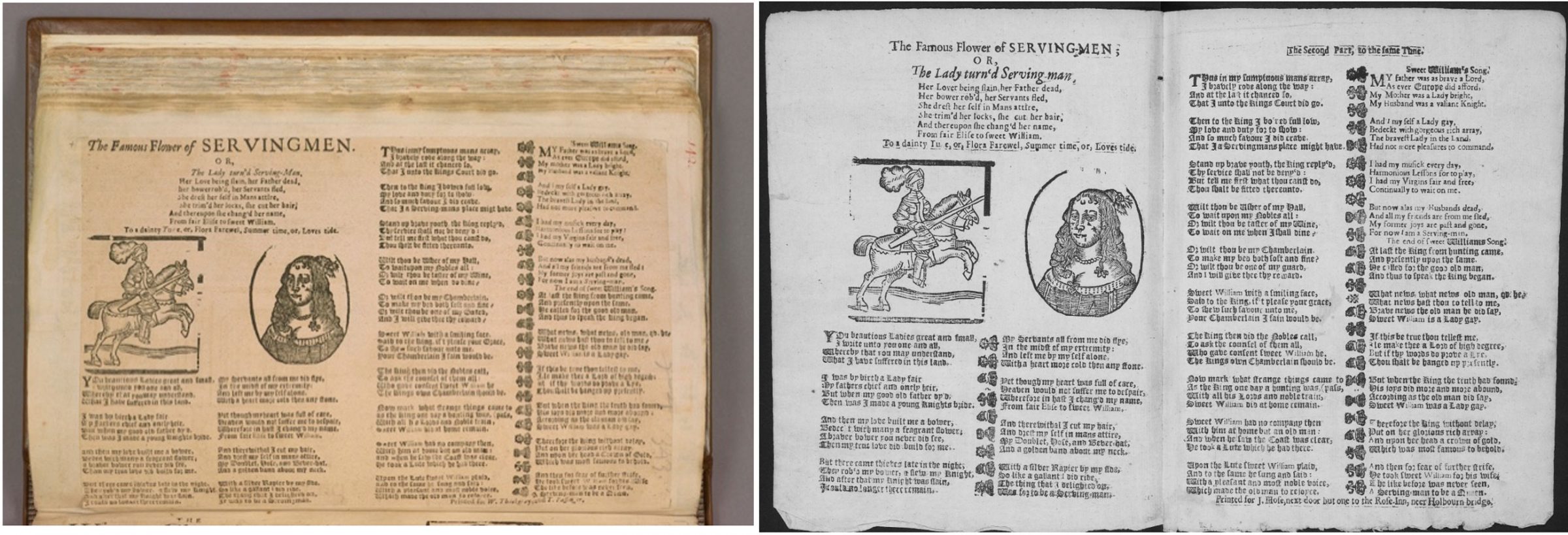

A gentleman brandishes a sword and rides a prancing steed, a youth with bobbed hair doffs his hat, and a buxom lady with a knowing gaze shows just a hint of a smile. These figures, appropriately fairy tale-esque when described in a group, adorn an early printing of the popular broadside ballad, “The Famous Flower of Serving-Men,” and represent a still remarkably understudied subset of ballad culture in this period: the ballad woodcut.

According to the University of California at Santa Barbara’s English Broadside Ballad Archive (EBBA),[1] the ballad was originally composed by Lawrence Price, one of the few named balladeers with a “popular following”[2] whose ballads first are found in print in the 1620s and 1630s.[3] The ballad appeared in at least five distinct seventeenth-century printings from at least three printers, was published in the nineteenth-century Child Ballads collection,[4] and even inspired successful modern renditions. The earliest edition seems to be a printing by John Andrews, estimated by EBBA to date to between 1654 and 1663. Its seventeenth-century text stays remarkably consistent,[5] tracing an essentially identical plot: a young woman (usually named Elise, with variants including Alice and Eliza) is her father’s sole heir, and is married to a “young Knight” (8). This knight is then slain and the bower he built for Elise is destroyed by thieves. The protagonist “in haste” changes her name to “sweet William” and alters her gendered presentation as she “cut[s] [her] hair” and dons “Mans attire” (23, 24, 25). “Sweet William” then enters the service of the king and sings a song (a ballad) recalling “his” life as “Elise,” which leads an eavesdropping “old man” to tell the king “Sweet William is a Lady gay” (97). The king then dresses William/Elise in “glorious rich array,” marries her, and makes her queen, in time for the ballad’s satisfying end (107). This plot is full of recognizably early modern tropes and plot scripts: a young woman engages in female-to-male crossdressing with titillating results, the tension of which is resolved into marriage. Reversals of fortune are reversed again, rewarding a virtuous protagonist.

Upon closer examination, however, the ballad presents a more complex thematic landscape extending beyond these familiar gender politics and the predictable critical readings we might assign them. These more predictable, of course, follow a vital tradition in Renaissance literary scholarship, stemming from its 1980s turn to gender and feminist critique. This critical movement, while pivotal for addressing the oversights in previous early modern scholarship, did not fully unpack the equally important politics of class and race in Renaissance texts, and it is this type of multivalent politic that I will discuss in the context of that “Famous Flower.”

By permission of the Pepys Library,

Magdalene College, Cambridge.

I. Critical Traditions and Woodcuts in the “Famous Flower”

In the 1980s and 1990s, Renaissance scholars were motivated by the political landscape of second- (and third-) wave feminism, responding to provocative works such as Joan Kelly’s “Did Women Have a Renaissance?” with a burst of new feminist scholarly work. They demanded attention to women’s writing, thought, and lived experience in the period.[6] Literary critics considered androgyny, crossdressing, so-called “women’s work,”[7] and Renaissance humoral theories—all politically charged topics for the feminist movement that were harnessed for scholarly work in the Renaissance.[8] Crucially, as I will discuss, considerations of class remained noticeably absent from this 1980s and 1990s scholarly turn. In ballad scholarship, texts such as Diane Dugaw’s survey of crossdressing ballads, Warrior Women and Popular Balladry 1650–1850 (1989)[9] and Joy Wiltenburg’s Disorderly Women and Female Power in the Street Literature of Early Modern England and Germany (1992) turned this feminist-inflected gaze on the cheap print of the period.[10] Here too, scholars produced gender-inflected readings of broadside ballads, chapbooks, and other ephemera, but notably, they did not fully consider how class might be fitted into these issues. Dugaw’s research focused on the “gender masquerades” of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century crossdressing ballads, examining “Female Warrior” characters who were at once “paragon[s] of virtuous love” and “patriotic, courageous [and] adventurous.”[11] While Dugaw connected these warrior women to a notion of “lower class experience,” her work (like much scholarship from this period) did not use these class claims to drive her examination of gender transgression. Texts such as Wiltenburg’s discussed the “popularity” of cheap print texts and their class-marked consumer bases, but these questions of consumption often sat as prefaces to the gendered readings that followed them, and class analysis did not mingle with the feminist analyses of balladic plots and characters.

From the 2000s, retrospective analyses of 1980s and 1990s criticism noted the limitations of such scholarly work, but again, still failed to turn directly to questions of class. In 2007, Dympna Callaghan discussed the phases of Renaissance feminist critique and countered charges that Renaissance feminist scholarship had “run its course.”[12] After charting the opposing theses of “exclusion” and “revisionism” in feminist scholarship on the early modern period, Callaghan noted the critical “impasse” due to this conflict, and suggested that early modern feminist scholarship might instead “[couple] with … a range of other political and intellectual projects as it takes its rightful place in the intellectual mainstream.”[13] But Callaghan’s call, while important, did not articulate the specific political stakes for these intellectual projects, including the ways that Renaissance feminist critique might incorporate class alongside its gender analyses.[14] While feminist scholars discussed how class hierarchies in the early modern period influenced the capacity of women to write, consume, and influence literature and culture, this focus did not result in a class-driven feminist scholarly approach. Thus critiques (like Callaghan’s) of feminist scholarship, while valid, do not, I think, go far enough. For Renaissance feminist scholarship to truly become a political force once again, it must intentionally and explicitly consider issues of class as they intersect with gender.

The post-2016 political landscape, however, offers early modernists an opportunity to revisit this vital but unfinished critical work. The era of Brexit and Trump has brought renewed attention to class in public discourse, and scholars, including Andrew Hadfield in this volume, have been quick to consider how this might inform their academic work (and, in Hadfield’s case, why we might have failed to fully consider class up to this point).[15] This political context has forced us to confront (in Renaissance studies and elsewhere) the unfulfilled promises of both feminist politics and scholarship and to think about how feminist and gender-motivated scholarship must engage with class. We might return to Renaissance texts themselves to see the ways gender analysis is always already class analysis (and vice versa), a relationship that we can frame in the present moment’s language of “intersectionality.” Seventeenth-century ballads like “Famous Flower” are particularly useful, as their image/text interplay (a kind of media-intersectionality itself) brings together gender- and class-motivated tropes. In this essay, I will talk about such multimedia signaling in “Famous Flower” and consider its class disruption alongside its crossdressing. My image-oriented analysis also emphasizes how digital scholarship is vital to these repoliticized critical efforts. In order to move ahead with freshly politicized class/gender cross-readings, we must harness the digital tools and political frameworks of the present day, to push forward an early modern scholarship that is intersectional in its ideology and its methodology.

But what makes the English broadside ballad an effective site for multimedia readings of class/gender interplay in the period? Early ballad scholarship often downplayed any relationship between the ubiquitous woodcut image and the ballad itself,[16] and only more recently have scholars such as Patricia Fumerton and Sarah Williams begun to consider the woodcut as central to understanding ballad culture.[17] Williams rightly ties increasing scholarly interest in ballad woodcuts to the rise in digitized accessibility and cataloguing of ballads, noting that the “scholarly lacuna [of ballad woodcut scholarship] existed until around 2003 when the advent of EEBO (Early English Books Online) fostered an increase in the interdisciplinary scholarship on the multimedia nature of broadside ballads.”[18] While significant scholarship has explored the interaction of image and printed text in the early modern period, it is perhaps a mark of the still emerging field of ballad scholarship that (with a few exceptions) such critical consensus has not yet extended to the broadside ballad.[19]

To return now to “Famous Flower,” I will show how this ballad’s woodcuts open up an intersectional gender/class logic, one we can access through digital work. Like many crossdressing plot-scripts of the early modern period, the ballad trades on Elise/William’s harnessing of her own androgynous appeal as a “Serving-Man” to the King.[20] This moment, while perhaps now familiar in its gender dynamics, is deeply radical on the level of class: a king and a servant take equal part and equal pleasure first in the fluid class-posturing (represented by the roles of “usher,” “taster of my wine,” etc., initially suggested by the King), and then implicitly in a sexual encounter. This series of events ends in the former “Serving-Man’s” marriage to the king, and her elevation to the status of “Queen.” Still, this radical class displacement and mobility are difficult for us to disentangle from the gender fluidity that may first demand our attention, and which represents the more traditional site for critical, political attention. We are further encouraged in this gendered reading as we consider “William’s” “sweetness,” which recalls the erotic language of young male androgyny.[21] It is this aspect of the ballad that we are perhaps more ready to explore, thanks to the tradition of gender-oriented (but not class-focused) scholarship I have previously discussed. The ballad’s woodcuts, however, pointedly return us to its class-oriented concerns, connecting them to the more readily available gender-transgressive script. Thus, if we seek to reinvigorate the feminist/gender-politic of 1980s and 1990s early modern critique, we must turn to these woodcuts, considering their own “intersectional” seventeenth-century mode as we address the need for greater intersectionality in our own work. Reading “Famous Flower” with its woodcuts helps us see the equal interests that this ballad has in class-as-titillation and gender play, and more broadly, how the slide between gender and class transgression might be made pleasurable through association with the cultural anxieties surrounding both issues.

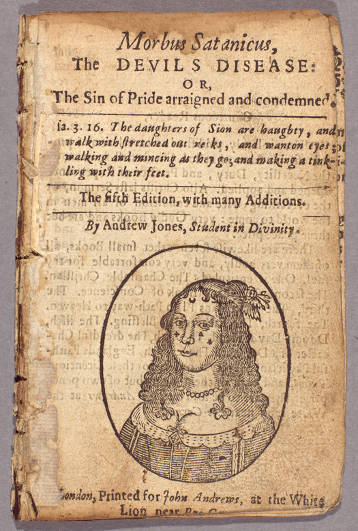

I will begin by considering one image as it appears in the 1654 John Andrews printing of the ballad. The image, which I call “Woman with Patches,” depicts a young woman in an oval portrait frame, presented at a three-quarter turn. Her expression is pleasant, with a decidedly knowing gaze, and her attire is à la mode for the mid-seventeenth century. With a significant amount of loose, flowing hair, and an ample bosom on display, the figure is an emphatically female one. This femininity is accentuated by the “patches,” or symbols drawn with cosmetics, on the figure’s face (although, as I will discuss, this cosmetic cover-up can also suggest pox from venereal disease). The image also shows two flowers dangling from the woman’s hair—a particularly literal touch connecting it with the titular “Famous Flower” of the ballad. Moving left to right, “Woman with Patches” is the third image one encounters on the Andrews broadside, and it is situated definitively in the ballad’s “Second Part.” She is situated opposite an apparently male figure in a square woodcut of roughly the same size, and each seems to head a column of this “Second Part.” By this logic of orientation, the male figure tracks roughly with the line “Stand up brave Youth the king reply’d,” while “Woman with Patches” is implicitly associated with the section of “Sweet Williams Song” that recalls “And I my self a Lady gay, / Bedeckt with gorgeous rich array” (41, 78-79). While it is impossible to speak with confidence about printer intentionality here, these two images correspond smoothly to the lines that sit immediately beneath them. The male figure on the left provides a satisfying, male-attired “brave Youth,” while the figure on the right shows us the “Lady gay” in her “rich array,” giving us present-William and then past-Elise as we move from left to right. Reading these images onto the ballad’s characters in this way is made easy by the youthful appearance (and bobbed hairstyle) of the figure on the left, as well as his bowing posture (“bowed full low”) (37). This male figure could be understood to be a different character from the ballad (the old man or perhaps the king), but these seem unsatisfying identities when compared with the “brave youth,” William. Thus, as we read or view this ballad, we may flip back and forth between “William” and “Elise” as we engage with these images, moving between genders and thus also between the different classes of “Lady” and “Serving Man.” Still, this initial analysis leaves open the question of what the highly feminized image of “Woman with Patches” is doing in a text that, in other ways, seems so invested in the androgynous appeal of the boyish “William” and the class-transgressive potential of a servant who catches the eye of the king, engages sexually with him, and ultimately marries him.

EBBA 31819. By permission of the University of Glasgow

Library, Special Collections.

II. The Politics of Patches

To answer this question, it is crucial to first understand how “Woman with Patches” is not simply an incidental choice, but rather trades on a visual language of cosmetics and elaborate hairstyles as markers of female economic consumption. This woodcut depicts not just a woman of a certain class, but rather a woman who allows us to think about class. Clare Backhouse has noted that this image as it appears in “Famous Flower” is reminiscent of (and may in fact have been inspired by) an engraving by Thomas Cross that appeared in Francis Hawkins’s 1652 Youths Behaviour, where it is part of a pair of satirical oval engravings, and is clearly labelled “VICE.”[22] This is not, however, the most prominent print locus of “Woman with Patches.” In addition to its inclusion in “Famous Flower,” it is a woodcut that has a prominent other life in a non-ballad text, as well as a clear reprint value in the ballad itself. While “Woman with Patches” appears more than once in printings of “Famous Flower,” a repetition to which I will return presently, it carries a significantly stronger ongoing association with another text: “Morbus Satanicus, The DEVILS DISEASE: OR, The Sin of Pride arragned and Condemned.” This religious chapbook appeared in various printings over at least three decades in the mid- to late-seventeenth century, seeming first to have been printed around 1656—approximately the same time that John Andrews printed “Famous Flower”— by the same John Andrews. The text itself is a brief and pious enumeration of the dangers of pride, including “in the habit and apparel of the body.”[23] In other words, it seeks to provide a religious antidote to the spiritual dangers of luxury consumption. The chapbook features Biblical injunctions against pride and luxurious materialism, and ends with “one most fearful example” about a vain Dutch woman who, after employing cosmetics and fine clothes to make herself beautiful, is killed by the devil and subject to gruesome bodily decay (with perhaps a suggestion of venereal disease). The text concludes with this admonishment: “ all that reads or hears of this incident, especially all those who delight in painting and decking themselves up in pride, as this proud person did… may behold and see their own sins, and be ashamed of their evil ways.”[24] The chapbook provides moral instruction for a popular reader against the sin of pride and establishes luxury consumption as the locus for this sin. “Woman with Patches” becomes an integral part of this effort as an example of class-disruptive consumption, and can be seen as a depiction of the sinful “Antwerp woman,” or, more broadly, as one of “those who delight in painting and decking themselves up.” Indeed, the author cleverly situates the text’s most “fearful example” of this behavior in Holland, a prime site in the English imagination for concerns about the purchase power and social disruption of a newly wealthy middle class. “Morbus Satanicus” thus trades upon a sense of the class-destabilization inherent in the purchasing of luxury garments and cosmetics. “Woman with Patches” becomes a representation of a reader of the text whose behavior needs to be corrected , and who improperly engages in sinful, class-transgressive economic consumption.

There are at least seven distinct extant editions of “Morbus Satanicus” (later editions of the text claim on the title page that there are at least thirty-six such editions) spanning from the 1650s to the 1680s, and all but one feature “Woman with Patches” on their title page.[25] Early editions are printed by John Andrews, our “Famous Flower” printer, and subsequently Elizabeth Andrews (presumably a wife or daughter who carried on the business after his death). Later printings are usually associated with William Thackeray and/or Peter Brooksby, although not exclusively with these names. These individuals were prominent printers/publishers of both chapbooks and broadside ballads so, on a logistical level, the imagistic connection between “Morbus Satanicus” and “Famous Flower” makes sense. Still, there is more here than just a printer reusing an in-house woodcut, as the print trajectory of “Morbus Satanicus” illustrates. Even when, between the 1667 and the 1677 printings, the name of the author changes from “Andrew Jones” to “William Jones,” and is no longer listed as a “student of divinity,”[26] the image associated with the text stays the same. “Woman with Patches” is maintained through various printers, an obvious attempt to maintain visual continuity through various printings, and one of the 1677 printings uses what seems to be a reproduction of the original woodcut, as can be seen in the differences in the shape of the woman’s eyes, mouth, lace trim, shading, and the shape of the frame.[27] By the 1685 printing (the last extant copy), the front woodcut is no longer “Woman with Patches,” but maintains almost all of its distinguishing traits: pearl necklace, abundant curls, ample cleavage, and most significantly, at least one patch (a half-moon) on the figure’s face.

By permission of the Huntington Library.

Thus, for seventeenth-century readers, the particularities of this image as associated with the text are perhaps more important than any other print considerations. The “sinful” associations of “Morbus Satanicus” can help us see what is so compelling about “Woman with Patches” itself, and by extension, how this understanding can bring us back to the class-based concerns of “Famous Flower.” The popular chapbook’s imagistic connection to the ballad gives us a way of fully reading what might have initially seemed to be the ballad’s secondary concern—its engagement with class fluidity. Here, “Woman with Patches” becomes critical to our understanding of “Famous Flower,” and to our understanding of ballads generally as printed texts that not only encourage, but also rely upon image/text cross-reading.

This image, as I have previously suggested, is deeply engaged with issues of economic consumption, particularly with the implications of luxury consumption that might be considered frivolous or prideful—spending on clothing, jewelry, and particularly cosmetics and hair ornaments. In a way that is particularly apt for the concerns of “Famous Flower”, however, these concerns do not stay squarely within the realm of economic anxieties, even religiously-charged ones. The consumption of items like the cosmetics used to make the patches on “Woman with Patches” also had profound implications for the sexual standing of the individual in question. As the ballad “A Description of Bartholomew-Fair” reminds us, patches were often associated with venereal disease. This ballad advises those who visit the fair that they may encounter extravagant accessories like “Gloves [and] Ribbond” for purchase, as well as the dangerous underside of fine dressing, or “Fine Ladies with patches, and powder’d with pox.”[28] “Bartholomew-Fair” evokes a typical tension between the “fineness,” or aristocratic associations, of cosmetics and their decidedly undesirable use in covering up scars, most particularly those caused by syphilis, or “pox.” Such decoration thus held “low” associations with prostitution, a connection that appears frequently in ballads where patches are mentioned, as well as unnecessary expenditures associated with female pride.[29] This pull between prideful consumption of goods and sexual deviancy is again one that is already present in “Morbus Satanicus.” Thus, the presence of “Woman with Patches” on “Famous Flower” latches onto the ballad’s more obvious questions about sexuality and sexual behavior but evokes these in a context that is also necessarily economic and class-based, bringing our readerly attention to this second set of concerns, even as it utilizes our knowledge of the former set.

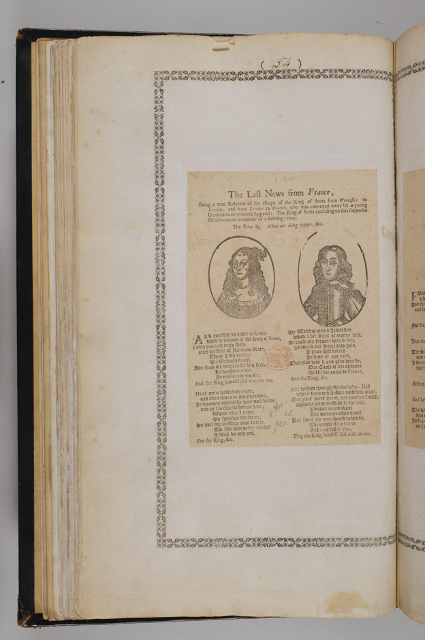

The afterlife of “Woman with Patches” does not end with “Morbus Satanicus.” She appears prolifically in other ballads as well, particularly in those printed by William Thackeray and/or Thomas Passinger. Although, as I will discuss below, there is no centralized way to digitally map the full extent of the woodcut’s spread, I have thus far discovered ten distinct ballads that use this woodcut from these two printers alone, with particular help from the English Broadside Ballad Archive’s “Woodcuts” image association tool. While it certainly seems that “Woman with Patches” had an active circulatory life, it was by no means the only frequently-used female woodcut, or even portrait-shaped female woodcut by these printers. Rather, an exploration of these ballads yields further evidence of what we have already seen in the connection between “Famous Flower” and “Morbus Satanicus”—that “Woman with Patches” gained, through a web of imagistic connections and cultural associations, a sort of symbolic status.[30] The woodcut could act as a titillating shorthand for balladic crossdressing, class transgression, and sexual promiscuity, even though the image itself carries no direct reference to the first two, and only a potential association with the third. One particularly fine example of this power comes in a ballad called “The Last News from France, / Being a true Relation of the escape of the King of Scots from Worchester to / London, and from London to France, who was conveyed away by a young / Gentleman in womans Apparel.”[31] In a manner similar to what we have seen with “Famous Flower,” “Woman with Patches” is alongside a noble male figure (the non-crossdressed king) in a manner that seems to suggest that “Woman with Patches” is thus (humorously, daringly, and transgressively) the pretty king in drag.

55). EBBA 30402.

As we turn to later printings of “Famous Flower,” “Woman with Patches” continues to appear, beginning with a printing by Thackeray and Passinger that EBBA dates to the mid- to late-1680s.[32] As we saw in its “Morbus Satanicus” trajectory, “Woman with Patches” gains prominence in later editions of “Famous Flower,” moving from a secondary placement above the ballad’s second half, to a prime location below its title. This same shift also occurs in another, nearly identical printing by John Hose (which Bodleian Ballads Online gives an even earlier print date, around 1670).[33] In the both printings, “Woman with Patches” is no longer a header for the “Lady” that “Sweet William” describes in his song, but appears on the ballad’s first page, located directly across from this ballad’s only other woodcut.[34] When we factor in the intertextual logic evoked by “Woman with Patches” and its class- and sexuality-based associations, this change takes on a greater significance. The seventeenth-century ballad consumer, one who might be familiar with the “Morbus Satanicus” iteration of “Woman with Patches”, would read her image not just as a “Lady fair,” but as evoking possible sexual deviancy, in conjunction with consumption, dress, and cosmetics. “Woman with

III. Digital Woodcuts and Searching the Broadside Ballad

Now that we have seen how image/text relationships like those between “Woman with Patches” and “Famous Flower” are crucial for understanding the multimodal work of ballads and their accompanying woodcuts, particularly in the case of this woodcut’s class-mobile associations, I would like to turn a critical lens to the digital methodologies that can enable this sort of analysis, focusing specifically on sites like UCSB’s English Broadside Ballad Archive, and considering Sarah Williams’s claim that digital platforms like these have allowed ballad woodcut scholarship to emerge as a viable scholarly avenue. I will explore how sites such as EBBA, EEBO, and the Bodleian Library’s Broadside Ballads Online allow a new scholarly interplay between ballad text and ballad image, and I will detail the digital pathways I followed in tracing one ballad and its accompanying woodcut. Furthermore, I will consider the limitations these sites have for woodcut-oriented ballad work, their role in unpacking the multivalent gender/class politic of the broadside ballad, and their capacity to reinvigorate our own critical agendas.

I will begin by tracing the paths I followed, first in pursuit of “Famous Flower” variants and then in search of the “Woman with Patches” woodcut. As is common with present day ballad scholarship, I began my inquiry into “Famous Flower” print variants with a search of EBBA’s archive, using the site’s “Advanced Search,” which allows searches by ballad title, author, and full text, all of which can be used to triangulate print variants of a ballad like “Famous Flower.”[35] EBBA has done significant work in crafting a site whose digital interface addresses the multimodality of ballads, allowing visitors to collate results thematically, by print context (searching by printer, addressing the frequent anonymity of the broadside ballad), and, crucially, by tune, addressing the aurality of ballads. Among other options, EBBA allows for an “author” search; in the case of “Famous Flower,” this allows us to see that “Woman with Patches” appears with our “Famous Flower” author (Lawrence Price) on another ballad, “Give me the Willow-Garland,” whose printers are also late printers of an edition of “Morbus Satanicus.”[36]

As we have seen, however, criticism on ballad woodcuts is arguably the least developed area of ballad scholarship, and thus it is not surprising that, until recently, this has been the area in which EBBA’s search functionality was most limited. In the case of my project, which began in the fall of 2015, there was initially no direct method by which to cross-reference my search findings on “Famous Flower” with a focus on its woodcuts, or even with a series of descriptors of the image’s properties. In this earlier stage, EBBA was careful to acknowledge the woodcut image as a significant entity, featuring an image search function called “EBBA Woodcut/Impression Keyword” which searched by pre-set image category.[37]

EBBA’s initial interface thus necessitated that I search entry by entry, looking for matching woodcuts, and while categories like “women/woman” (yielding 900 results) gave a manageable subset through which to search, the process was still not comprehensive. Still, this method did allow for a uniquely ballad-esque orientation, privileging other modalities over the textual when exploring the vast spread of ballad literature. This search allowed me to see the ways in which “Woman with Patches” is class-transgressive, in ways that more keyword-targeted searches (for example “patches”) might not bring to the fore, bringing up ballads like “Renowned ROBIN HOOD,” where “Woman with Patches” is used presumably to represent the ballad’s Queen Katherine.[38]

Searching EBBA’s holdings for images, while relatively far-reaching for digital ballad work, does not allow us to cross-reference our hits with other comparable forms of cheap print. Thus, if we are invested in the kind of cross-referencing that might truly allow us to understand the cultural capital of an image like “Woman with Patches,” we must also use one of the more comprehensive and commonly-used databases of early modern facsimile: Early English Books Online. Despite its field-changing role in broadening digital access to early modern texts, however, EEBO is not well suited to address the image components of early modern cheap print, even given its significant holdings in this category. Printer-based searches using our initial findings from “Famous Flower” are most effective here, and it was through this method that I initially encountered “Morbus Satanicus.” Again, while this technique is clunky and far from comprehensive, it can help harness the network of related cheap print texts which intersected at nodes of printers, authors, and woodcuts. EEBO’s great strengths in terms of text/image ballad scholarship are its wide holdings and its spread across various cheap print forms, allowing greater access to chapbooks like “Morbus Satanicus.” We can also see the ways in which EBBA, through its comprehensive ballad-oriented records, allows us to use a broader site like EEBO in more precise ways.

Until recently, the Bodliean’s Broadside Ballads Online offered perhaps the most technically-advanced search function for investigations of ballads’ text/image relationship. The site’s “ImageBrowse” page was based on ImageMatch work done by Oxford’s Visual Geometry Group, was released on their site in November of 2014,[39] and represented a significant step forward in woodcut-oriented ballad scholarship, allowing some of Bodleian’s ballad holdings to be searched directly by image.[40] While “Image-Browse” currently only searches Broadside Ballads Online’s relatively modest sample of approximately 900 of about 1,600 pre-1701 broadside ballads, a search of just these holdings returned (through multiple searches) as many as thirteen exact matches of “Woman with Patches”, as first seen in the Andrews printing of “Famous Flower.” These findings cement the mobility, but also the specificity of an image like this one, which appeared frequently but with precisely class- and gender-coded associations that augmented the ballads with which it was seen. A search of a single woodcut image, like “Woman with Patches” turns up ballad broadsides that “ImageBrowse” can in turn search as an image in full, or by “region” (section). This search, for example, shows that “Woman with Patches” seems to have been favored by printer Peter Brooksby. While this name appears in some EBBA/EEBO searches, he is given greater prominence through this Bodleian Ballads Online search, and we can see again ongoing image associations with female sauciness and promiscuity.[41] While Broadside Ballads Online’s image search functions are, of course, not foolproof (particularly with image reproductions of poor quality from sites like EEBO), they represent an increasingly important approach to ballad criticism, presenting woodcuts themselves as a fruitful starting point for ballad scholarship.[42] [AR2]

The cross-referencing and thematic potential of the Bodleian’s site then brings us to a similar and even more significant innovation introduced by EBBA in late fall of 2017. This function, labelled “Search by Woodcut,” allows users (much like the Bodleian site) to follow image pathways across ballads, to access groups of similar woodcut images and thus to work comparatively across ballad woodcuts. Perhaps most crucially, EBBA’s impression archive will ultimately allow users to search across the large collection of its ballad holdings, which (as of August 31, 2020) contain over 9,300 ballads.[43]

Unlike Bodleian Ballads Online, EBBA’s site does not prompt users to begin exclusively with an image, but rather offers two avenues through which users may approach its woodcut holdings. These options, which I will discuss in detail here, offer tantalizing possibilities of how we might assemble networks of the kinds of image/text connections seen between “Woman with Patches” and “Famous Flower,” and which may uniquely illuminate the potential of this cross-media reading to bring out ballads class transgressivity, as well as other forms of political play. EBBA offers an “upload” function, similar to that offered by Bodleian Ballads Online, but University of California, Santa Barbara’s site also notes that users may “click on the “Woodcuts” tab from any ballad view to see all occurrences of the woodcut impressions on any ballad.”[44] This dual approach is in keeping with EBBA’s ethic site-wide, placing the multimodal ballad at its center, and as Patricia Fumerton observes, “remediat[ing] ‘original’ artifacts by making them more accessible precisely through the hypermedia of multiple facsimiles, metadata, and recordings”—and to this list we might add ballad woodcuts themselves.[45] Such an approach also allows users to arrive at ballad woodcuts in a variety of ways, including by tune, printer, or date range. A simple search by EBBA ID (title, full text, or ESTC Number could also be used) allowed me to arrive at “Famous Flower” once again, and from there navigate to EBBA’s standard multi-tab ballad page, which now contains an added “Woodcuts” tab. From this tab, I was able to find an individualized representation of each woodcut image in the broadside (in the case of the Andrews printing, this included the broadside’s largest woodcut image, a man on horseback, as well as our gentleman bowing and, of course, “Woman with Patches”).[46] EBBA thus uses its own image-recognition interface to create a similar cross-referencing effect to the Bodleian’s site, connecting the woodcuts identified in each ballad with others across its archive (again, this is an extremely powerful tool given EBBA’s large and still-expanding archive size). In the case of the Andrews printing of “Famous Flower,” this meant that it was possible for me to find instances of each woodcut across EBBA’s holdings, and to follow each woodcut image in various other sites of appearance. I might also have arrived at a similar “Cluster” by uploading a cropped image solely of “Woman with Patches.” Considering the many instances of this woodcut, I found confirmation of the pathways I had already established manually through (albeit painstaking) searches of the site. The speed and ease of this kind of network-based image exploration, however, allowed me to quickly identify another, similar image to “Woman with Patches,” one that I might call “Woman with Patches 2.” This woodcut is paired with “Woman with Patches” in a ballad engaging again with issues of cosmetics and sexually promiscuous behavior, entitled “The Innocent Country Maid’s Delight…” The second woodcut, much like “Woman with Patches,” features a “patched” woman with abundant décolletage in a round frame, and according to the Impression Archive, appears in even more of EBBA’s holdings than “Woman with Patches.” This new woodcut, then, gives us an idea of precisely the sorts of paired and continuing image analyses that EBBA’s new image software can yield. We might, to return to my earlier call, be able to use woodcuts like this one to explore the broad class-transgressive scope of ballad broadsheets capitalizing on the dual associations of class-transgressive consumption and gender play, bringing class into our consideration of gender across these ballads, and giving a newly political edge to ballad scholarship generally.

Perhaps the most tantalizing part of EBBA’s new image work is its addition of “tags” and “categories” that are associated with each image. While these labels currently provide some simple contextual and associative markers for an image, they also suggest a future possibility for further networked searches, where users can view all of EBBA’s woodcut images that are tagged in this way. These new search functions also raise other exciting possibilities, like the possibility of tracing pairs or groupings of multiple images that, while not yet available, are evocatively suggested by these new features. EBBA’s latest project certainly affirms ballad woodcuts as both an area of promising new research, and a place in which the digital platforms necessary to such research are beginning to materialize and grow in sophistication. This image-recognition technology begins to build webs of visual connectivity, helping us craft complex maps of woodcuts that might be seen in conjunction with each other, and trace the kinds of ballads with which they might be associated. Thus, we may navigate and recombine analyses in what Patricia Fumerton calls the “countless dis-memberings or fragmentations” which “[approximate] the early modern period’s own access to its printed materials.”[47]

We have thus seen how the digital tools I have discussed can both aid in and present challenges for the type of repoliticized, cross-thematic and cross-media work I demonstrated with “Woman with Patches” and “Famous Flower.” While this ballad and woodcut are particularly fascinating instances of the role that a woodcut can play in inflecting ballad gender-play with an equally crucial class component (and by extension, bring our critical attention to such interplay in the period), they are far from the only cheap print/woodcut pairing that works in this way. Rather, they allow us to see, returning to Sarah Williams’ claim, how digital tools like EBBA and the Bodleian Ballad Archive are newly suited to foster these politicized, image-oriented readings. Using these tools can allow us more easily to trace the image/text cross-reading which may yield texts’ most transgressive elements, such as the sorts of class movement seen in “Famous Flower,” which were so integral to the early modern experience of these print forms. This kind of digital scholarship can thus help us pursue scholarly avenues that are intrinsically political, as they bring to light the early modern “intersectionality” of cheap print, seen in both the multimodal intersections inherent in ballads and other ephemera, and in their savvy slippages between issues like gender and class. These forms reiterate the scholarly necessity of such intersectionality in our own time. Digital scholarship thus provides an important first step in repoliticizing our criticism of ballads and of cheap print in the period, even as we acknowledge that, both now and in the foreseeable future, texts like the broadside ballad may still present a more subtle and fluid politic than even these exciting new tools can show.

Works Cited

“A Description of Bartholomew-Fair. [London]: Printed for F. Coles, T. Vere, J. Wright, J. Clarke, / W. Thackeray and T. Passinger, 1680. English Broadside Ballad Archive. Pepys Ballads 2.58. R 227339.

“Animtas and Claudie: / Or, The Merry Shepherdess, / Shewig whatever he from Vertue did not draw, / She circumvented with a ha, ha, ha.” London: Printed for VV. Thackeray, T. Passenger, and VV. Whitwood. [1678-1688]. English Broadside Ballad Archive. National Library of Scotland—Crawford. Crawford. EB.199.

“The Bashful Virgin: / Or, / The Secret Lover.” London: Printed for W. Thackeray, T. Passenger, and W. Whitwood. [1678?]. English Broadside Ballad Archive. Magdalene College – Pepys. Pepys Ballads 4.30.

Callaghan, Dympna. “Introduction.” In The Impact of Feminism in English Renaissance Studies. Ed. Dympna Callaghan. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007. 1–29.

Daston, Lorraine and Katherine Park. Wonders and the Order of Nature, 1150–1750. New York: MIT Press, 1998.

Dugaw, Diane. Warrior Women in Popular Balladry, 1650–1850. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1989.

Fumerton, Patricia. “Introduction: Multimedia and Multimodal Theatricality.” In Ballads and Performance: The Multi-Modal Stage in Early Modern England. Ed. Patricia Fumerton. Santa Barbara: emcIMPRINT, 2018.

Fumerton, Patricia. “Remembering by Dismembering: Databases, Archiving, and the Recollection of Seventeenth-Century Broadside Ballads” In Ballads and Broadsides in Britain, 1500–1600. Eds. Patricia Fumerton and Anita Guerrini. Surrey: Ashgate, 2010. 14–34.

—. Unsettled: The Culture of Mobility and the Working Poor in Early Modern England. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006.

Hadfield, Andrew. “Class, Politics, and Renaissance Literature.” In Politics and Early Modern Criticism in a Time of Crisis. Ed. David Baker and Patricia Palmer. Santa Barbara: EMC Imprint, 2020.

“ImageMatch and researching ballad contexts” Bodleian Ballads Online, last modified 8 April, 2014. https://balladsblog.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/blog/1071.

“Introducing Bodleian Ballads ImageBrowse” Bodleian Ballads Online, last modified 11 November, 2014. https://balladsblog.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/blog/1069.

Jones, Ann Rosalind and Peter Stallybrass. Renaissance Clothing and the Materials of Memory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

Jones, Andrew. “Morbus satanicus, = the devils disease.” London: printed for John Andrews, at the White Lion near […1656?]. Wing (2nd ed.) / J920A. pg. 3.

—. “Morbus satanicus, = the devils disease: or, The sin of pride arraigned and condemned. The sixteenth edition with many additions. By Andrew Jones, student in Divinity.” London: For Elizabet Andrews in St. Bartholomews-Court in West Smithfield, 1667; EEBO. Wing (2nd ed.) / J922.

—. “Morbus satanicus, = the devils disease: or, The sin of pride arraigned and condemned. The tenth edition with many additions. By Andrew Jones, student in Divinity.” London: For Elizabeth Andrews, at the White Lion near Pye Corner, 1662; EEBO. Wing (2nd ed.) / J921.

—. “Morbus satanicus, = the devils disease: or, The sin of pride arraigned and condemned. The 21st edition with many additions. By Andrew Jones, student in Divinity.” ([London]: For W. Thacke[r]ay, at the sign of the Angel in Duck-lane 1674); Beinecke Digital Collections. Bound with Jones, Andrew, M.A. “The black book of conscience, London, 1660.” 10191729

—. “Morbus satanicus, = the devils disease: or, The sin of pride arraigned and condemned. The 36 edition with many additions. By William Jones, student in Divinity.” [London] : Printed by H.B. for J. Clark, W. Thackery, and T. Passinger, 1685; EEBO. Wing / 1911:20

Knapp, James A. “The Bastard Art: Woodcut Illustration in Sixteenth-Century England.” In Printing and Parenting in Early Modern England. Ed. Douglas A. Brooks. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate, 2005. 151-72.

Kelly, Joan. “Did Women Have a Renaissance?” In Women, History & Theory: The Essays of Joan Kelly. Paperback Ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986. 19–50.

“The Last News from France, / Being a true Relation of the escape of the King of Scots from Worchester to / London, and from London to France, who was conveyed away by a young / Gentleman in womans Apparel.” London: Printed for W. Thackeray. T. Passinger, and W. Whitwood [1678?]. English Broadside Ballad Archive. British Library—Roxburghe. C.20f.9.54-55.

McShane, Angela. “‘Ne sutor ultra crepidam’: Political Cobblers and Broadside Ballads in Late Seventeenth-Century England.” In Ballads and Broadsides in Britain, 1500–1600. Ed. Patricia Fumerton and Anita Guerrini. Surrey: Ashgate, 2010. 208–28.

Park, Katherine. Secrets Of Women: Gender, Generation, and the Origins of Human Dissection. Brooklyn: Zone Books, 2006.

Paster, Gail Kern. The Body Embarrassed: Drama and the Disciplines of Shame in Early Modern England. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1993.

Price, Lawrence. “Give me the VVillow-Garland; / Or, The Maidens Former Fear, and Latter Comfort. / At first she for a Husband made great moan, / But at the last she found a loving one.” ([London]: For F. Coles, T. Vere, J. Wright and J. Clarke; English Broadside Ballad Archive. Magdalene College. Pepys Library. Pepys Ballads 3.94. R234418.

—. “The Famous Flower of SERVING-MEN. / OR, / The Lady turn’d Serving-Man.” London: For John Andrews, at the White Lion near Pye-Corner, [1654?]; English Broadside Ballad Archive. University of Glasgow Library. Euing Ballads 111. R176942.

—. “The famous flower of serving-men; or, the lady turn’d serving-man.” [London]: Printed for J. Hose, next door but one to the Rose-Inn, neer Holbourn-bridge, [1670?]. Bodleian Ballads Online. ESTC: R14853.

—. “The famous Flower of Serving-men. / OR, / The Lady turned to be a SERVING-MAN.” [London]: Printed for W. Thackeray and T. Passin[g]er [1686?]; English Broadside Ballad Archive. Magdalene College. Pepys Ballads 3.142.

Rackin, Phyllis. Shakespeare and Women. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Shakespeare, William. Twelfth night, or What You Will. In The Riverside Shakespeare. Ed. G. Blakemore Evans. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1974. 408–42.

“Renowned ROBIN HOOD: Or, / His Famous Archery truly related, with the Worthy Exploits he acted before / Queen Katherine, being an Out law-man, and how he for the same obtained / of the King, his own, and his Fellows pardon.” [London]: Printed for J. W., I. C., W. T. and T. Passinger [1681?]; English Broadside Ballad Archive. Magdalene College. Pepys Ballads 2.103. R234302.

Simpson, Claude. The Broadside Ballad and its Music. New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 1966.

Wall, Wendy. Staging Domesticity: Household Work and English Identity in Early Modern Drama. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

Watt, Tessa. Cheap Print and Popular Piety, 1550–1640. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994.

Williams, Sarah F. Damnable Practices: Witches, Dangerous Women, and Music in Seventeenth-Century English Broadside Ballads. Surrey: Ashgate, 2015.

Wiltenburg, Joy. Disorderly Women and Female Power in the Street Literature of Early Modern England and Germany. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1992.

Woodbridge, Linda. Women and the English Renaissance: Literature and the Nature of Womankind,1540–1620. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1984.

Wurzbach, Natascha. The Rise of the English Street Ballad, 1550–1650. Trans. Gayna Walls. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

Zemon Davies, Natalie. “Displacing and Displeasing: Writing about Women in the Early Modern Period.” In Attending to Early Modern Women. Ed. Susan Dwyer Amussen. Newark: Associated University Presses, 1998.

Image Citations:

1. Price, Lawrence. “The Famous Flower of SERVING-MEN. / OR, / The Lady turn’d Serving-Man.” (London: Printed for John Andrews, at the White Lion near Pye-Corner, [1654?]); English Broadside Ballad Archive. University of Glasgow Library. Euing Ballads 111. R176942.

2. Carthy, Martin. “Martin Carthy VRC0392 The Famous Flower Of Serving Men.” Filmed February, 1996. Youtube video, 11:48. Posted 21 November, 2012. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_00g-asQvVk.

3. “Renowned ROBIN HOOD: Or, / His Famous Archery truly related, with the Worthy Exploits he acted before / Queen Katherine, being an Out law-man, and how he for the same obtained / of the King, his own, and his Fellows pardon.” ([London]: Printed for J. W. I. C. W. T. and T. Passinger [1681?]); English Broadside Ballad Archive. Magdalene College. Pepys Ballads 2.103. R234302.

4. “Cornell Conference on Women 1969.” By Mann Library [CC BY-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons.

5. Chambers, Stephen. Step 4. March 3, 2014. RA Magazine. https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/article/learning-by-making

6. “THE / Famous Flower of Serving-Men. / OR, / The Lady turn’d Serving-Man.” (London: Printed and Sold in Bow-Church-Yard, London); English Broadside Ballad Archive. National Library of Scotland. Crawford Ballads Crawford.EB.1384.

7. Deverell, Walter H. “Twelfth night: det.: left figure.” 1849-1850. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3ADeverell_Walter_Howell_Twelfth_Night_Act_II_Scene_IV.jpg

8. Price, Lawrence. “The Famous Flower of SERVING-MEN. / OR, / The Lady turn’d Serving-Man.” (London: Printed for John Andrews, at the White Lion near Pye-Corner, [1654?]); English Broadside Ballad Archive. University of Glasgow Library. Euing Ballads 111. R176942.

9. Ibid.

10. Jones, Andrew. “Morbus satanicus, = the devils disease: or, The sin of pride arraigned and condemned. The fifth edition, with many additions. By Andrew Jones, student in divinity.” (London : printed for John Andrews, at the White Lion near […1656?]; EEBO. Wing (2nd ed.) / J920A. pg. 3.

11. Jones, Andrew. “Morbus Satanicus. The devils disease. Or the sin of pride arraigned and condemned. The 27 edition with many additions. By William Jones, student in Divinity.” (London : printed, by W.L. and T.J. for W. Thackery, T. Passenger, P. Brooksby, J. and Williumson, 1677.); EEBO. Wing .

12. Image Set images from:

Jones, Andrew. “Morbus satanicus, = the devils disease: or, The sin of pride arraigned and condemned. The fifth edition with many additions. By Andrew Jones, student in Divinity.” (London : printed for John Andrews, at the White Lion near […1656?]; EEBO. Wing (2nd ed.) / J920A.

Jones, Andrew. “Morbus satanicus, = the devils disease: or, The sin of pride arraigned and condemned. The sixteenth edition with many additions. By Andrew Jones, student in Divinity.” (London : printed for Eliz. Andrews in St. Partholomews-Court in West Smithfield, 1667.); EEBO. Wing (2nd ed.) / J922.

Jones, Andrew. “Morbus satanicus, = the devils disease: or, The sin of pride arraigned and condemned. The 21 edition with many additions. By Andrew Jones, student in Divinity.” ([London] : printed for VV. Thacke[r]ay, at the sign of the Angel in Duck-lane 1674); Beinecke Digital Collections. Bound with: Jones, Andrew, M.A. “The black book of conscience, London, 1660.” 10191729

Jones, Andrew. “Morbus Satanicus, the devils disease, or, The sin of pride arraigned and condemned by William Jones. The 25 edition :with many additions.” (London: Printed by W.L. and T.J. for W. Thackery, Phil. Brooksby, John Williamson and J. Hose, 1677.) EEBO. Wing / J923A

Jones, Andrew. “Morbus satanicus, = the devils disease: or, The sin of pride arraigned and condemned. The 36 edition with many additions. By William Jones, student in Divinity.” ([London] : Printed by H.B. for J. Clark, W. Thackery, and T. Passinger, 1685); EEBO. Wing / 1911:20

13. “ENGLANDS PRIDE, / OR, / A Friendly Exhortation to forsake that Sin so much in Request. / The Proud are God Almighties Foes, / yet that Sin is too rife; / But why should Sinners thus oppose / that God that gave them life.” ([London]: Printed for J. Deacon, at the Sign of the Angel in / Gilt=Spur=Street. [1672-1702]); English Broadside Ballad Archive. National Library of Scotland–Crawford. R176711.

14. Image Set Images from:

Price, Lawrence. “The Famous Flower of SERVING-MEN. / OR, / The Lady turn’d Serving-Man.” (London: Printed for John Andrews, at the White Lion near Pye-Corner, [1654?]); English Broadside Ballad Archive. University of Glasgow Library. Euing Ballads 111. R176942.

“The famous flower of serving-men; or, The lady turn’d serving-man” (London: Printed for J. Hose, next door but one to the Rose-Inn, neer Holbourn-bridge. [c. 1670]); Broadside Ballads Online. Bodleian Library. Ballad – Roud Number: 199. Shelfmark Wood E 25(75).

“A Tragical Story of / LORD THOMAS / And Fair Ellinor. / Together with the Downfall of the Brown Girl.” ([London]: Printed for I. Clark, W. Thackeray, and T. Passenger. [1684-1686]); English Broadside Ballad Archive. Magdalene College–Pepys. R187594.

“A Courtly New Ballad of the Princely Wooing of the fair maid of London, by King Edward.” ([London]: Printed for I. Clarke, W. Thackeray, and T. Passinger. [1684-1686]); English Broadside Ballad Archive. Magdalene College–Pepys. R174356.

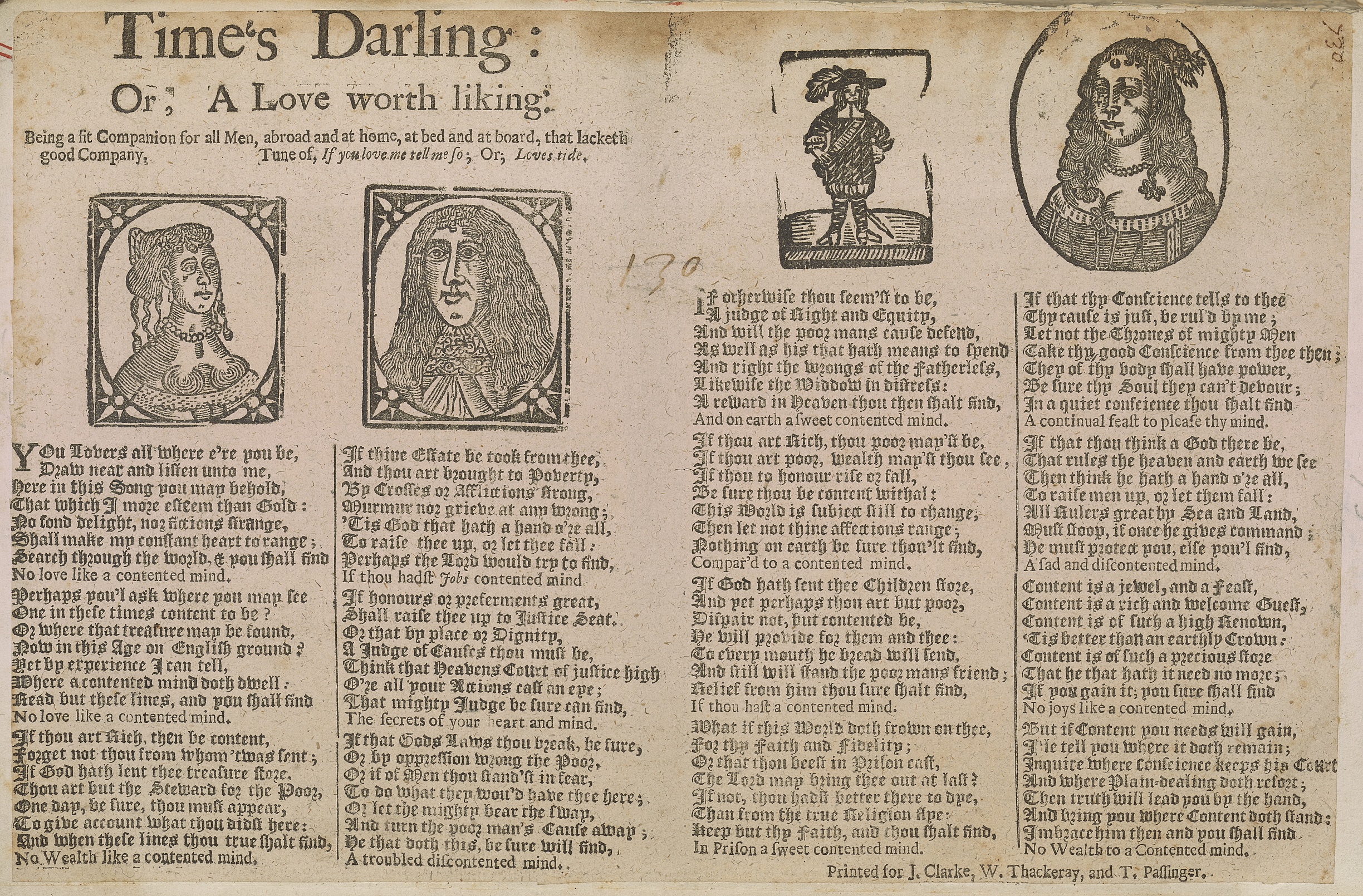

“Time’s Darling: / Or, A Love worth liking: / Being a fit Companion for all Men, abroad and at home, at bed and at board, that lacketh / good Company.” ([London]: Printed for J. Clarke, W. Thackeray, and T. Passinger. [1684-1686]); English Broadside Ballad Archive. Magdalene College–Pepys. R234238.

Price, Lawrence. “The Famous Flower of SERVINGMEN. / OR, / The Lady turn’d Serving-Man.” (London: Printed for W. Thackeray, and T. Passin[g]er., [1686-88]); English Broadside Ballad Archive. Magdalene College–Pepys. R188038.

Price, Lawrence. “Give me the VVillow-Garland; / Or, The Maidens Former Fear, and Latter Comfort. / At first she for a Husband made great moan, / But at the last she found a loving one.” ([London]: Printed for F. Coles, T. Vere, J. Wright, and J. Clarke. [1674-1679]); English Broadside Ballad Archive. Magdalene College–Pepys. R234418.

“Renowned ROBIN HOOD: Or, / His Famous Archery truly related, with the Worthy Exploits he acted before / Queen Katherine, being an Out law-man, and how he for the same obtained / of the King, his own, and his Fellows pardon.” ([London]: Printed for J. W. I. C. W. T. and T. Passinger [1681?]); English Broadside Ballad Archive. Magdalene College. Pepys Ballads 2.103. R234302.

“The Bashful Virgin: / Or, / The Secret Lover. / Cupid hath wounded her unto the heart, / Which makes her feel a Love tormenting smart, / Yet she (poor heart) is loath for to discover / Her real grief unto her dearest Lover, / At length she courage takes, and doth reveal / What she long time intended to conceal.” (London: Printed for W. Thackery, T. Passenger, and W. Whitwood.[1678-1688]); English Broadside Ballad Archive. Magdalene College–Pepys. R226991.

“The Young-Mans Complaint for / The Loss of his Mistris. / Young-men you see my Fortune is such, / I have lost my Love by loving her too much: / My fortune’s bad as other Young mens be, / Read but these Lines, and you shall Plainly see: / I being bashful, she did me quite forgo, / I have lost my dear Mistris by being too slow.” ([London]: Printed for J. Wright, I. Clark, W. Thackeray,/ T. Passinger, and M. Coles.. [1680-1682]); English Broadside Ballad Archive. Magdalene College–Pepys. R187785.

15. “The Last News from France, / Being a true Relation of the escape of the King of Scots from Worchester to / London, and from London to France, who was conveyed away by a young / Gentleman in womans Apparel.” (London. Printed for W. Thackeray. T. Passinger, and W. Whitwood [1678?]). English Broadside Ballad Archive. British Library – Roxburghe. C.20f.9.54-55.

16. Price, Lawrence. “The famous Flower of Serving-men. / OR, / The Lady turned to be a SERVING-MAN.” ([London]: Printed for W. Thackeray and T. Passin[g]er [1686?]); English Broadside Ballad Archive. Magdalene College. Pepys Ballads 3.142.

17. Price, Lawrence. “The famous flower of serving-men; or, the lady turn’d serving-man.” ([London]: Printed for J. Hose, next door but one to the Rose-Inn, neer Holbourn-bridge, [1670?]). Bodliean Ballads Online. ESTC: R14853.

18. From English Broadside Ballad Archive, ed. Patricia Fumerton. (https://ebba.english.ucsb.edu).

19. Ibid.

20. Ibid.

21. Ibid.

22. Ibid.

23. Ibid.

24. Ibid.

25. Ibid.

26. Ibid.

27. Ibid.

28. Ibid.

29. From Early English Books Online. (https://eebo.chadwyck.com/home).

30. Ibid.

31. From Broadside Ballads Online, from the Bodleian Libraries. (https://ballads.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/)

32. Ibid

33. Ibid.

34. Ibid.

35. From English Broadside Ballad Archive, ed. Patricia Fumerton. (https://ebba.english.ucsb.edu).

36. Ibid.

37. Ibid.

38. Ibid.

39. Ibid.

40. GIF image from: Price, Lawrence. “The Famous Flower of SERVING-MEN. / OR, / The Lady turn’d Serving-Man.” (London: Printed for John Andrews, at the White Lion near Pye-Corner, [1654?]); English Broadside Ballad Archive. University of Glasgow Library. Euing Ballads 111. R176942. Edits by Katharine Landers, 2017.