[I]f the work of critique does not show that its object can be undone, or promise to undo its object, then what is the point of that critique?

— Sara Ahmed, “A Phenomenology of Whiteness”

There is thought, but before it is unthought: a mode of interacting with the world enmeshed in the “eternal present” that forever eludes the belated grasp of consciousness.

— N. Katherine Hayles, Unthought: The Power of the Cognitive Nonconscious

This collection is animated by an uncomfortable question: how, amid the “cascading crises of our era,”[1] can early modernists persist in imagining that they have something useful to bring to conversations increasingly transfixed by a planetary emergency? Still, our introduction suggested that a crisis in the very way we think about crisis is part of that wider crisis – and that attending to discourses in crisis is one thing early modernists can do. Discourses that had already run out of steam in addressing earlier manifestations of crisis (around gender, race, colonialism, sexuality, for example) seem to have even less to offer when confronted with the intensifying existential threats of our time. And that epistemological crisis is also a crisis of the imagination: we struggle both to produce a critique of the present and to imagine a future different from the dystopian prospects that transfix us. That epistemological crisis – the breakdown in explanatory frameworks which the Introduction enjoins us to push through and treat as incentives to think harder and afresh – has some points of overlap with Cathy Caruth’s account of trauma. The sense that “no discourse is adequate here”, to quote Judith Butler as we did in the Introduction, has some kinship with “the breach in the mind’s experience of time, self, and the world” characteristic of trauma. Trauma, Caruth explains,

is always the story of wound that cries out, that addresses us in the attempt to tell us of a reality or truth that is not otherwise available. This truth, in its delayed appearance and its belated address, cannot be linked only to what is known, but also to what remains unknown in our very actions and our language.[3]

But, for the early modernist, unlike the trauma theorist, the precious “unknown” that can connect past to present and thereby make sense of both was once known; it has simply fallen out of the present field of knowledge. In the now strange and unfamiliar things it has sequestered, the past offers us the forgotten rather than the unknown; it confronts what is “unthought” in the present with what was once eminently thinkable. The task of mediating between these two temporalities of knowing and forgetting is a task for the early modernist. What once fell out of history, becoming something long “unthought,” can “even now,” to quote Derek Mahon, turn out to be “places where a thought might grow.”[4]

Stephen Rae reads Derek Mahon’s “A Disused Shed in Co. Wexford”

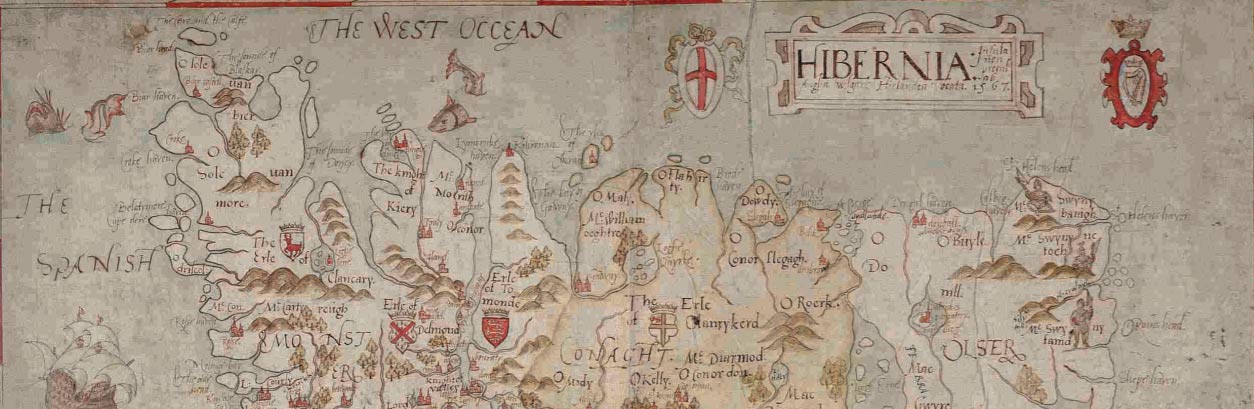

This coda is intended as a trial piece, a little experiment in engaging with a poem that, ostensibly, comes from one of the cul-de-sacs of history, a poem that takes for granted something that was becoming, even as it was being written, an “unthought,” something no longer thinkable — a sense that the world is animate. The poem, Mo chean duitsi, a thulach thall, composed in the early 17th century by a bardic poet, Laoiseach Mac an Bhaird, who outlived the fall of his civilisation, comes to us dusty from its 400-year immurement in a bypassed tradition, a poem of grief written in the most hieratic register of Classical Irish. But the poem’s address and orientation to the more-than-human — to a tree, the very thing which, until very recently, would have merely confirmed its status as a historical thought-fossil, suddenly repositions it anew on readers’ “horizon of expectation.”[5] In groping towards a methodology for thinking with what has been long been “unthought,” I reflect, too, on the place of translation and the digital humanities in that process of recovery.

In trying to think his way beyond the Cartesian bracketing-off of “nature” as a res extensa — a res extensa ripe for emergent capitalism to exploit — Bruno Latour suggests that “there is no way to devise a successor to nature, if we do not tackle the tricky question of animism anew.”[6] Returning to Latour’s thought-provoking assertion, already aired in the Introduction, that “we are actually closer to the sixteenth century than to the twentieth century,”[7] this coda attempts to tackle that “tricky question of animism” by bringing us back to a distinctly pre-modern — pre-Cartesian, pre-Baconian — understanding of how people, power, and the natural world intersect. Laoiseach Mac an Bhaird’s Mo chean duitsi, a thulach thall (titled “On Cutting down an Ancient Tree” by its early twentieth-century editor)[8] is what used to be known as “a curiosity.” Framing its marginalisation in terms of Rancière’s “partage du sensible,” it may seem like just another needle lost in the haystack of the “insensible.” In Barthean terms, it is “il-lisible.”[9] It is certainly little read.[10] So why not leave it where it is, just another poem fallen out of history? One good answer is given by Adrienne Rich:

because in times like these

to have you listen at all, it’s necessary

to talk about trees.[11]

Rich’s “What Kind of Times Are These” brings us to an all-too-familiar place of disenchantment where a “dark mesh of the woods” is in the sights of a developer “who wants to buy it, sell it, make it disappear.” Its trees are out of time, precarious survivors in a “ghost-ridden” world that is haunted by “shadows,” “dread,” and “the persecuted / who disappeared into those shadows.” Mac an Bhaird’s Mo chean duitsi, a thulach thall, “Salutations to you, o hill over there,” probably written in the years after 1600,[12] is also set in a time of persecution and disappearances. But it brings us to a worldview where that which has become merely a “ghost,” a “shadow,” by Rich’s time of “truth and dread” survives, however terminally, as a force that infuses trees with something besides xylem and phloem and endows hills with a responsiveness to direct address. So, to the poem, first in the original and then in translation:

Deirdre Nic Chárthaigh reads “Mo chean duitsi, a thulach thall.”

1. Mo chean duitsi, a thulach thall,

fád thuisleadh ní subhach sionn;

damhna sgíthi do sgeach dhonn,

cleath chorr do-cíthe ós do chionn.2. Sgeach na conghára, crádh cáigh,

na háit comhdhála do-chínn,

buain na craoibhe, mo lá leóin,

daoire ’na dheóidh mar tá an tír.3. Dubhach mo chridhisi um chum

fád bhilisi, a thulach thall;

an chleath ó bhfaicinn gach fonn,

do sgeach chorr ní fhaicim ann.4. Do bhíoth dhamh ag dénaimh eóil,

an ghégsoin fá gar do mhaoin;

fada siar ón tírsi thuaidh

aníar uaim do-chínnsi an gcraoibh.5. An ghaoth ar bhfoghal a fréamh,

craobh gan bhloghadh doba buan;

ní tearc neach dá ndearna díon,

sníomh na sgeach fá teadhma truagh.6. Gég chruthach bá corcra lí,

mé dubhach má dol fá dhlaoi;

mairg nár smuain ar dhaoirsi nDé,

’s go bfuair mé fád chraoibhsi caoi.7. Do teasgadh ar n-aoinchreach uainn,

an chaoimhsgeach dob easdadh d’eón;

sgé a samhla níor fhás a húr,

dhúnn go bás badh damhna deór.8. Mo chréidhim go bruach mo bháis,

mo-nuar nach éirghionn ar-ís;

ní fhaicim cnoc na gcleath gcnuais

nach gluais lot na sgeach mo sgís.9. Cnoc na gconghár, crádh na sgol,

a n-orláimh námhad a-niodh;

d’éis a learg as dubhach dhamh,

tulach ghlan do chealg mo chion.

Mo chean duitsi was edited by the great Celtic scholar Osborn Bergin and collected in his Irish Bardic Poetry, a volume which has done more than any other publication to bring Classical Irish poetry to a non-specialist audience. The corpus he effectively created through the selections he made for his “Unpublished Irish Poems” series continues to define bardic poetry for early modernists working without or with only some Irish.

Bergin’s accompanying translation, first published in 1926, now adds its own patina of age — those hails and wonts and yonders and thys, those syntactical inversions, those ejaculations and exclamation marks — to a poem already out of time.[13] It is at once invaluable and a confirmation that translation and re-translation is itself vital to the project of bringing the past back into the present:

1. Hail to thee, O hill yonder: at thy fall I am not joyous; thy brown thorn is a cause of woe, the smooth stem that was wont to be seen above thee.

2. The thorn of acclamation, a torment to all, I used to see as a place of assembly: the cutting of the branch, my day of sorrow! the state of the land is baser thereafter.

3. My heart in my breast is sad for thy ancient tree, O hill yonder; the stem from which I was wont to see each tract, thy smooth thorn I see not there.

4. That bough was wont to guide my way — it was a transient possession! — far back from this land in the north I could see in the distance the branch behind me.

5. The wind has ravaged its root, that branch so long unshattered; many was the man it sheltered; a woeful plague was the destruction of the thorn.

6. Shapely bough of ruddy hue, I am sad it has gone under a wisp; woe to him who has not thought of the sufferings of Christ, since I have found occasion to weep for this branch.

7. It has been cut away, our utter ruin! the comely thorn that was a storehouse for the bird; a thorn like it never grew from the soil; to me until death it will be a cause of tears.

8. My gnawing pain to the brink of my death, alas that it rises no more! Never do I see the hill of the fruitful stems but that the ruin of the thorn stirs my sorrow.

9. The hill of the shoutings, torment of the schools, in the possession of enemies to-day! After its slopes sad to me is the fair hill that hath pierced my affection.

More recently, the poem was translated by Bernard O’Donoghue, for The Penguin Book of Irish Poetry. The genius of O’Donoghue’s translation is that he remains faithful to the original while finding a near-metaphorical equivalence for its sentiments; his “The Felling of a Sacred Tree” is, at once, an interpretation and that paradoxical thing, a faithful reimagining. Bergin’s translation of the opening line, “Mo chean duitsi, a thulach thall”, “Hail to thee, O hill yonder”, cleaves scrupulously to the literal sense of the original (while ineluctably introducing the lexicon — “hail”, “O”, “yonder” — of late-stage English Romanticism). O’Donoghue’s “My condolences, hill up there” captures the spirit of the poet’s uncanny cathexis with the hill — and with the tree “that stood out green upon your crest” — while at the same time rehousing it in the easy colloquialism of Irish English.[14] My temerity in adding a third translation here is of a piece with my wider attempt to wrestle with how we can make the past re-enter the present afresh. My doggedly literal translation below is an attempt to go back to the original while, inevitably, responding to it through a sensibility shaped by the “times like these”. What could seem to be, 100 years ago, as nothing more than one Indo-European language’s idiomatic way with coordinates, for example, can arrest us with urgent semantic salience in the Anthropocene. So, Bergin translated

fada siar ón tírsi thuaidh

aniar uaim do-chinnsi an gcraoibh (4.3-4)

as “Far back from this land in the north I could see in the distance the branch behind me.” In so doing, he tidied away a set of cardinal directions which I drag back in:

far to the west of this northern land,

east of me I could see the thorn-tree.[15]

The reinstatement of those giddying compass points restores the coordinates of a sanctified landscape while reminding us of the Irish language’s preference for cardinal directions over body-relative or egocentric coordinates, with all that implies for whether we take our position from the environment, or orient the environment around us, to our left and right. Bergin’s translation of the first line of that quatrain as “That bough was wont to guide my way” positions the poet as a hardy orienteer, availing of the tree as a control point in his navigation of the landscape. “Do bhíoth dhamh ag dénaimh eóil” (literally “it used to be making knowledge to me”), however, locates the “knowledge,” “information,” “guidance” more actively in the tree. The preference for cardinal directions and the location of agency and knowledge in a tree are suggestive of what Robin Wall Kimmerer calls “the grammar of animacy.”[16] In the translation which follows, I cleave as closely as I can to the original rather than naturalising it within the norms of English – except, sadly, when it comes to form. Mac an Bhaird addresses a hill to commiserate with it on the loss of a thorn-tree using the elite form of syllabic verse known as dán díreach. To deploy a form habitually used to address a lord and patron to address a seemingly inert topographical feature is, I believe, part of the poem’s “grammar of animacy”. The tessellated wizardry of the original’s full, slant, and criss-crossing rhymes, its mesmeric patterns of assonance, consonance, and alliteration can, I think, be seen as a “poetics of animacy”, but, although I lay the translation out in verse form, I recognise that there is no way of recreating an English equivalence for such poetic conjuring.

1. Salutations to you, o hill over there,

your fall brings me no joy;

your blackened thorn[17] lays me low,

the trunk-spire I used to see above your head.2. Thorn tree of “shoutcries,”[18] anguish to us all,

I’m used to seeing it in its place of assembly;

the felling of that bough, my day of defeat,

the country a bondslave in its wake.3. My heart is heavy in my breast

for your venerated tree, o hill over there,

the trunk from which I surveyed every bit of ground,

your spiked thorn tree, I don’t see there.[19]4. It made things known to me,

that spar, that short-lived gift,[20]

far to the west of this northern land,

east of me I could see the thorn tree.5. The wind has pierced its root,

thorn tree so long sound,

many’s the one it sheltered,

the wrenching of the thorn a wretched pestilence.6. Shapely bough of purple lustre,

I grieve that it has gone under the wisp;

woe betide those who didn’t reflect on Christ’s bondage

while I lamented over this tree.7. It was hacked down, the one prey they could take from us,

the precious thorn tree, storehouse[21] for the birds,

a thornbush like no other growing on earth;

it will keep me crying, until I myself die.8. It will gnaw at me until the brink of death,

alas that it leafs no more;

I cannot see the hill of the fruitful tree

without the thorn tree’s destruction triggering my grief.9. The hill of assembly, to the anguish of the schools,

is today in enemy custody;

I pine after its slopes,

noble hill that snagged my love.

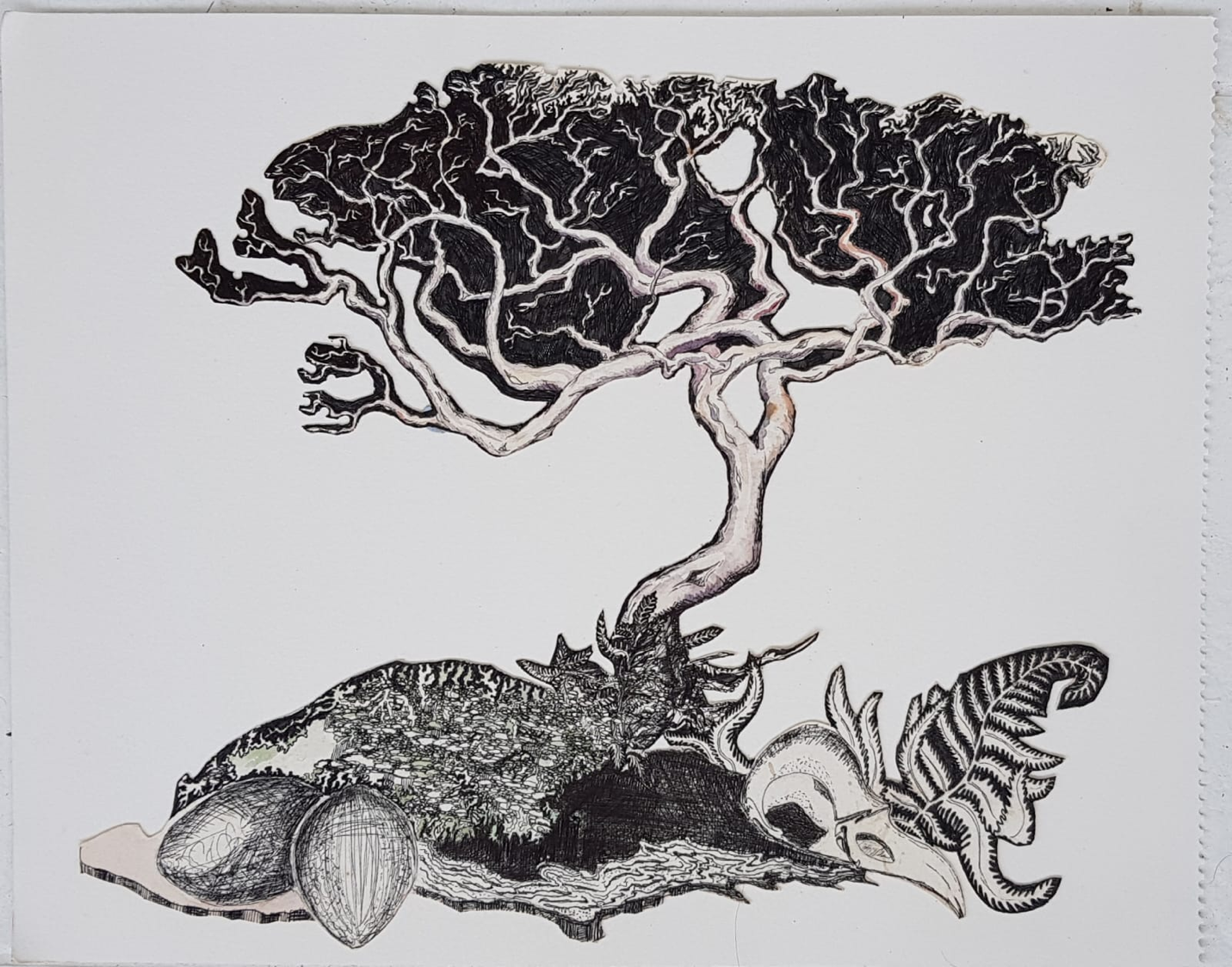

But even still, with the complex musicality of the original strained away by translation, this poem may not shock us; it may just underwhelm or ever so slightly disappoint us. So, it’s a nature poem, of a kind. We think we pick up a proto-ecological turn when it identifies the tree as a food-source for wildlife. Nonetheless, the extravagance of the response — a poet, shaken to his core, apostrophizing an inanimate hill and commiserating with it on the hewing down of a hawthorn (or blackthorn) — can seem overdetermined. But then, strangeness doesn’t always come at us in the form of the sublime. Sometimes, it’s the “nothing-to-see-here” reflex that blocks our view. But it’s worth pushing beyond this obstruction because what Mac an Bhaird elegises here is an understanding of interdependence that binds the land, the natural world, sovereignty, and poetry together in a way that can now, “in times like these,” seem both premodern and prescient.

Translating the poem from Classical Irish to modern English presents problems of semantic equivalence that border on being problems of epistemological equivalence. In the third quatrain, the tree is identified as a “bile” (you pronounce both syllables) which the Dictionary of the Irish Language defines as an “ancient and venerated tree.”[22] That veneration carried within it the residue of an older tradition of the sacred tree. “In Ireland, on the western extreme of the Celtic world, the emphasis seems to have been on individual venerated trees rather than on sacred groves. Such trees are referred to as bile or fidnemed.”[23] In mediaeval Ireland, the bileadha were seen as the “earthly sources of the poet’s wisdom,”[24] and something of that transference haunts Mac an Bhaird’s relationship with the desecrated tree. It was, in a very profound way, the source of his vision. The tree’s role as a wellspring of insight is worth exfoliating a little further.

Do bhíoth dhamh ag dénaimh eóil,

an ghégsoin fá gar do mhaoin (4.1-2);It made things known to me,

that spar, your gift for so short a while.

Here, the bile is identified as a “maoin,” a “gift” or “treasure,” where the word’s range of meaning extends, in literary usage, to “knowledge, science, art.”[25] Taken together with the allusion to the tree’s production of knowledge, discussed above as a crux in translation — “Do bhíoth dhamh ag dénaimh eóil” (“it used to be making things known to me”) — we find a cluster of allusions that associate the tree with understandings, however obscurely defined. It is no surprise, therefore, that it is the signal point from which the poet could see clearly, “an chleath ó bhfaicinn gach fonn” (3.3). It is no surprise either that its felling causes “crádh na sgol” (9.1), “anguish to the school” where “sgol” is a metonym for the literati trained in the bardic schools; their grief is consequent on the felling of a tree associated with poetic understanding.[26]

Just as poetry is rooted in — or routed through — the bile, a mycelial-like mesh of relations connects poet and tree to a third vertex in this complex triangular relationship: sovereignty. Mac an Bhaird calls the tree “Sgeach na conghára,” the whitethorn of “cries” or “clamours,” and identifies the hill on which it grew as a “place of assembly,” “áit comhdhála” (2.1-2). Bergin’s translation of “Sgeach na conghára” as “the thorn of acclamation” seems just right: it nails the identity of the hill apostrophized by the poet as a royal place of assembly, where the taoiseach of a lordship was inaugurated and proclaimed — acclaimed — by his people. Inauguration sites were ritual spaces, each endowed with a bile which symbolised both sovereignty and the sacred wisdom that sustained it.[27] The bile, rooted in a vestigial — and therefore quasi-metaphorical — sense of the chthonic as a source of legitimacy, figuratively channels the authority vested in both poet and lord. To hack it down it was to strike at the root of both sovereignty and the poetry which legitimised it. It was to enslave a people (to make them “daoir”, unfree, servile) and to reduce the land itself to “a possession of the enemy,” “a n-orláimh námhad” (2.4, 9.2), through a regime of extractive colonial capitalism that was already beginning to write its message on the land through deforestation.[28]

In his account of “The proceedings of the Earl of Essex, June 1600,” Francis Bacon recorded that the Earl had received clear instructions to go into Ulster “with great and puissant forces” to confront “the arch-traitor Tyrone” himself. (Hugh O’Neill, the Earl of Tyrone in English currency, led the Irish Confederate’s resistance to the conquest.) The verdict of the Privy Councillors was unanimous: “the axe should be put to the root of the tree.”[29] But when Essex, getting the measure of O’Neill’s seemingly unassailable power, diverted his forces to Munster instead, the Queen shot off a stinging reprimand, couched in the same metonymic terms, on 19 June 1599:

we must plainly charge you, according to the duty you owe to us, so to unite soundness of judgement to the zeal you have to do us service, as with all speed to pass thither in such sort, as the axe might be put to the root of that tree, which hath been the treasonable stock from whom so many poisoned plants and grafts have been derived. [30]

Now, the axes, literal and metaphorical, had fallen, and Mac an Bhaird found himself in an alien dispensation. He is an after-liver[31] in the new Baconian epistemology which Mauro Scalercio calls “imperiality.” Scalercio defines imperiality as “the power that humanity exerts over nature.” Imperiality is inherently expansionist and it intertwines itself naturally with colonialism, that “peculiar form of action inspired by knowledge.”[32] Bacon himself saw that entwinement clearly when his thoughts turned again to Ireland, in “Certain considerations touching the Plantation in Ireland, New year 1609.” In it, he celebrates the land which conquest has newly made available for planting as “endowed with so many dowries of nature, considering the fruitfulness of the soil, the ports, the rivers, the fishings, the quarries, the woods, and other materials.” One of the “great profit[s] for its new settlers will be the “liberty to take timber or other materials in your Majesty’s woods there.”[33]

And so, by a roundabout route, we come back to Latour’s “tricky question of animism,” and towards a conclusion that looks like it’s heading in the direction of a binary opposition. On the one hand, we have Bacon declaring that “nature is conquered only by obedience.”[34] On the other, we have Mac an Bhaird who, if we were to define him in Baconian terms, is steeped in the idola tribus, the “idols of the tribe” that Perez Zagorin glosses as “the intellect’s inclination to reify abstractions by attributing substance and reality to things in flux.”[35] Certainly, Mac an Bhaird’s understanding of the power vested in, rather than merely symbolized by, the bile and the hillside inauguration site fits the OED’s third sense of animism, “Belief in the existence of a spiritual world, and of soul or spirit apart from matter; spiritualism as opposed to materialism,” and it skirts its second sense, “The attribution of life and personality (and sometimes a soul) to inanimate objects and natural phenomena.”[36] Something of that attribution of life to an inanimate — or, rather, other-than-human — object ghosts Mac an Bhaird’s decision to frame his poem as a direct address, in the vocative, to a tradition-sanctified hill of assembly: “Mo chean duitsi, a thulach thall,” “Salutations to you, o hill over there.” Jonathan Culler argues that the figure of apostrophe always entails certain “vatic presuppositions” because of the way it “invokes elements of the universe as potentially responsive forces.” It represents, he suggests, “an atavistic casting of spells in the world.”[37] In Mac an Bhaird’s case, as we have seen, the channeling of quasi-magical energies is not so much atavistic as something recently and traumatically sundered. The tree that was so intimately bound up in the circulation of poetic and temporal power has, the poet tells us in the most enigmatic line in the poem, “gone under the wisp”: “mé dubhach má dol fá dhlaoi,” “I grieve that it has gone under the wisp” (6.2). An understandably puzzled Bergin can only suggest that this refers to “the druidic practice of chanting a spell over a wisp and throwing it at the victim.”[38] For the stricken poet, even the empirical fact of its felling needs to be recuperated by attributing it to magic. By the last couplet of the poem, the old connections have snapped. The poet no longer apostrophizes the hill; the vocative is over, and, in this newly disenchanted world, he is left alone with the singularity and anomie of his conflicting emotions:

d’éis a learg as dubhach dhamh,

tulach ghlan do chealg mo chion.

I pine after its slopes,

noble hill that snagged my love. (9.3-4)

Yet, even as Mac an Bhaird contemplates the intersecting ruination represented by the felling of the bile, he deploys the highest register of bardic poetry to enact and memorialize the quasi-animist interconnections that were being snapped asunder by conquest. In what I’m calling the poem’s “poetics of animacy,” its nine coiled quatrains replicate poetically the chain-link of connections that bind poet and ruler to the land through a shuttle-weave of assonance and phonetic replay, of internal and end rhymes, all stitched together by the oscillatory and translational motion of alliteration, audible in Nic Chárthaigh’s reading above.

But the animism-imperiality binary may not be as absolute as the Bacon-Mac an Bhaird face-off I seem to be positing suggests. Offering a gloss on the idola tribus, Perez Zagorin explains it as an error traceable to “the inveterate anthropocentrism with which human beings projected onto nature and the world the patterns of their own instinctual thinking.”[39] By that definition, Mac an Bhaird’s animism doesn’t escape anthropocentrism either. The natural magic of tree and hill are braided into institutions of human control, of kingship and poetry. Ultimately, they serve to power the power of others. Latour’s “tricky question of animism” is indeed, as Paul Muldoon says of history, “a twisted root.”[40] But that does not mean that premodern animist habits of thought have nothing to offer our sixth-extinction/global-heating present.[41] Graham Harvey defines animism as a “thoroughgoing relationship continuously negotiated through locally specific cultural etiquettes in a larger-than-human world.”[42] With the earth which we have been treating as inanimate for 400 years again reasserting itself as an active agent in our present — and in the future we’d hoped to have — the symbiotic and eco-systemic convictions of a poem like Mo chean duitsi enable it (because of, as much as in spite, of the anthropomorphic assumptions which ghost its animism) to rejoin a debate which has, paradoxically, caught up with its way of imagining the world.

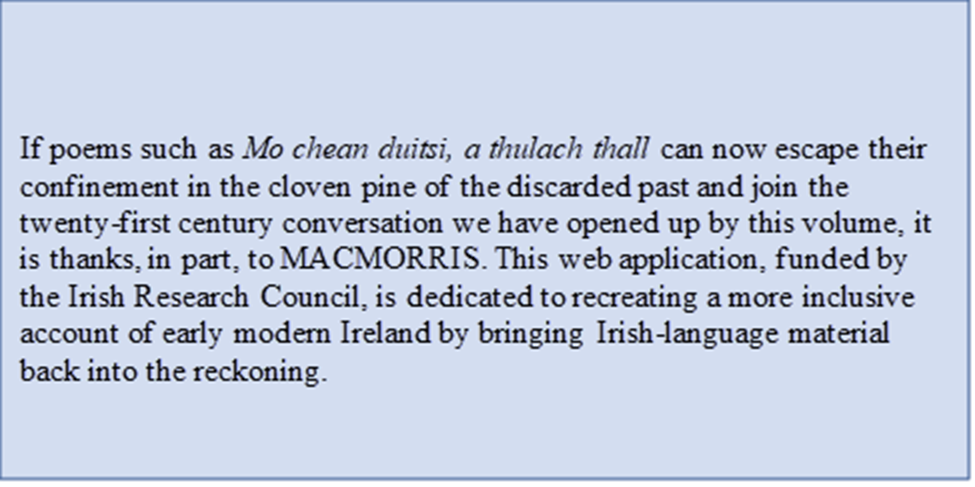

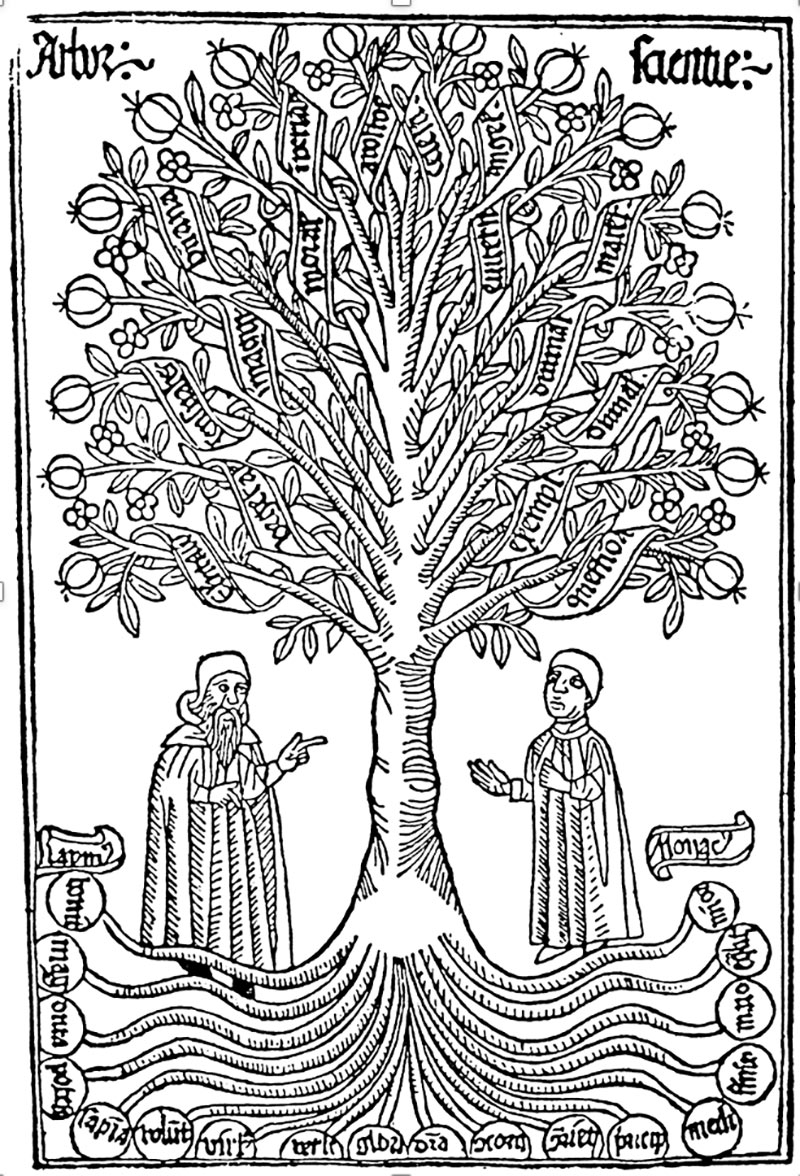

The thorntree in Mo chean duitsi, a thulach thall is, for its poet, a tree of knowledge. But it has something to teach us, too, about the politics of such acts of recovery and, specifically, the role which the digital humanities might have to play in rescuing such works and the long-“unthought” ideas which they encode — and, through that act of recovery, to enable them to join the twenty-first century conversation opened up by this volume. In seeking to explain the change of mindset involved in “the network turn”, Ruth Ahnert and her co-authors begin the book of that name by exploring the “rich conceptual and visual history” that, in framing, the “observable systems and phenomena in the world” have shaped, limited, opened, and reoriented “the questions we ask”. In particular, they explore “the epistemological repercussions of the shift from tree to network as the dominant visual system for charting systems of knowledge and information.” The mediaeval and early modern visual metaphor of the tree, they suggest, encoded a sense that “knowledge forms an absolute hierarchy.”

The network turn, in contrast, offers “an alternative to the arborescent conception of knowledge,” one that shows connections perspectivally and nonhierarchically. They proffer the rhizome metaphor of Felix Guattari and Gilles Deleuze’s 1980 book, A Thousand Plateaus, as “a model of knowledge that allows for multiple, non-hierarchical entry and exit points in data representation and interpretation.”[43] Mo chean duitsi, a thulach thall jumps — I won’t say bridges — the gap between the two modes of visualization by being a tree poem that is simultaneously arborescent (it is, after all, about a tree) and rhizomatic (it evokes a network of connections between earth, poetic inspiration, and authority). A “maoin,” a “gift” that is also a kind of “knowledge,” this little poem on the cutting down of an ancient tree offers us one small point of entry to an understanding of the world that does “not differentiate the order of knowledge from the order of being.”[44]

In doing so, this 400-year-old elegy for a thorn bush, addressed to a bereft hill, becomes a provocation to think harder not just about what is “thinkable” but about what is and isn’t “grievable.” By implicitly extending Judith Butler’s definition of an “ungrievable life” — a life “that cannot be mourned because it has never lived, that is, it has never counted as a life at all”[45] — to a tree, it can help us rethink and extend our definitions of what life-forms matter.

I am immensely grateful to Dr Deirdre Nic Chárthaigh and Dr Kevin Tracey of Maynooth University for their generous and enabling responses to a first draft of this Coda. And I would like to thank Professor Máirín Ní Dhonnchadha for helping me tease out my thoughts in a conversation early on in the process. I am keenly aware that what I offer here is only the start of a response to these scholars’ insights.

President Biden's use of the term in his Inauguration brought into wider circulation a term that is already recognized in scientific discourse. See, for example, the International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, special issue on "Understanding and mitigating cascading crises in the global interconnected system," 30 B (2018): 159-163.

President Biden's use of the term in his Inauguration brought into wider circulation a term that is already recognized in scientific discourse. See, for example, the International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, special issue on "Understanding and mitigating cascading crises in the global interconnected system," 30 B (2018): 159-163.

[1] Adrienne Rich, Dark Fields of the Republic (New York: Norton, 1995), 4.

[4] Latour, 480.

[4] Latour, 480.

[4] Latour, 480.

[4] Latour, 480.

[4] Latour, 480.

[4] Latour, 480.

[4] Latour, 480.

[4] Latour, 480.

[4] Latour, 480.

[16] Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants (2013; London: Penguin, 2020), 48.

[17] The poet offers little help with identifying the tree botanically. He refers to it throughout as a sgeach or sgé which the Electronic Dictionary the Irish Language defines as "a thorn bush, whitethorn" (dil.ie/36349). He never uses the word droighen, blackthorn. Yet, "donn," "dun-coloured," suggests the dark-barked blackthorn (Prunus spinosa) rather than the greyer bark of the hawthorn (Crataegus monogyna) – though, just to keep us guessing, 'donn' can also mean 'noble'. The tree's "Gég chruthach bá corcra lí," "Shapely bough of purple lustre" (6.1), similarly, evokes the bluish-purple bloom of sloes rather than the whitethorn's deep red haws. In the Brehon Law's seven-fold classification of trees, neither was one of the airig fedo," lords of the forest." The hawthorn was one of the "aithig fhedo," or "commoners of the forest," while the blackthorn found itself languishing among the fodla fedo, the "lower divisions of the wood". See Fergus Kelly, "Trees in Early Ireland," Irish Forestry: Journal of the Society of Irish Foresters 56 (1999): 39-57, 40-46.

[17] The poet offers little help with identifying the tree botanically. He refers to it throughout as a sgeach or sgé which the Electronic Dictionary the Irish Language defines as "a thorn bush, whitethorn" (dil.ie/36349). He never uses the word droighen, blackthorn. Yet, "donn," "dun-coloured," suggests the dark-barked blackthorn (Prunus spinosa) rather than the greyer bark of the hawthorn (Crataegus monogyna) – though, just to keep us guessing, 'donn' can also mean 'noble'. The tree's "Gég chruthach bá corcra lí," "Shapely bough of purple lustre" (6.1), similarly, evokes the bluish-purple bloom of sloes rather than the whitethorn's deep red haws. In the Brehon Law's seven-fold classification of trees, neither was one of the airig fedo," lords of the forest." The hawthorn was one of the "aithig fhedo," or "commoners of the forest," while the blackthorn found itself languishing among the fodla fedo, the "lower divisions of the wood". See Fergus Kelly, "Trees in Early Ireland," Irish Forestry: Journal of the Society of Irish Foresters 56 (1999): 39-57, 40-46.

[17] The poet offers little help with identifying the tree botanically. He refers to it throughout as a sgeach or sgé which the Electronic Dictionary the Irish Language defines as "a thorn bush, whitethorn" (dil.ie/36349). He never uses the word droighen, blackthorn. Yet, "donn," "dun-coloured," suggests the dark-barked blackthorn (Prunus spinosa) rather than the greyer bark of the hawthorn (Crataegus monogyna) – though, just to keep us guessing, 'donn' can also mean 'noble'. The tree's "Gég chruthach bá corcra lí," "Shapely bough of purple lustre" (6.1), similarly, evokes the bluish-purple bloom of sloes rather than the whitethorn's deep red haws. In the Brehon Law's seven-fold classification of trees, neither was one of the airig fedo," lords of the forest." The hawthorn was one of the "aithig fhedo," or "commoners of the forest," while the blackthorn found itself languishing among the fodla fedo, the "lower divisions of the wood". See Fergus Kelly, "Trees in Early Ireland," Irish Forestry: Journal of the Society of Irish Foresters 56 (1999): 39-57, 40-46.

[17] The poet offers little help with identifying the tree botanically. He refers to it throughout as a sgeach or sgé which the Electronic Dictionary the Irish Language defines as "a thorn bush, whitethorn" (dil.ie/36349). He never uses the word droighen, blackthorn. Yet, "donn," "dun-coloured," suggests the dark-barked blackthorn (Prunus spinosa) rather than the greyer bark of the hawthorn (Crataegus monogyna) – though, just to keep us guessing, 'donn' can also mean 'noble'. The tree's "Gég chruthach bá corcra lí," "Shapely bough of purple lustre" (6.1), similarly, evokes the bluish-purple bloom of sloes rather than the whitethorn's deep red haws. In the Brehon Law's seven-fold classification of trees, neither was one of the airig fedo," lords of the forest." The hawthorn was one of the "aithig fhedo," or "commoners of the forest," while the blackthorn found itself languishing among the fodla fedo, the "lower divisions of the wood". See Fergus Kelly, "Trees in Early Ireland," Irish Forestry: Journal of the Society of Irish Foresters 56 (1999): 39-57, 40-46.

[17] The poet offers little help with identifying the tree botanically. He refers to it throughout as a sgeach or sgé which the Electronic Dictionary the Irish Language defines as "a thorn bush, whitethorn" (dil.ie/36349). He never uses the word droighen, blackthorn. Yet, "donn," "dun-coloured," suggests the dark-barked blackthorn (Prunus spinosa) rather than the greyer bark of the hawthorn (Crataegus monogyna) – though, just to keep us guessing, 'donn' can also mean 'noble'. The tree's "Gég chruthach bá corcra lí," "Shapely bough of purple lustre" (6.1), similarly, evokes the bluish-purple bloom of sloes rather than the whitethorn's deep red haws. In the Brehon Law's seven-fold classification of trees, neither was one of the airig fedo," lords of the forest." The hawthorn was one of the "aithig fhedo," or "commoners of the forest," while the blackthorn found itself languishing among the fodla fedo, the "lower divisions of the wood". See Fergus Kelly, "Trees in Early Ireland," Irish Forestry: Journal of the Society of Irish Foresters 56 (1999): 39-57, 40-46.

[22] eDIL s.v. 1 bile or dil.ie/5885. See Michelle DiPietro, “Towards a cultural and chronological understanding of the Irish bile,” Ríocht na Midhe(2013): 1-28.

[22] eDIL s.v. 1 bile or dil.ie/5885. See Michelle DiPietro, “Towards a cultural and chronological understanding of the Irish bile,” Ríocht na Midhe(2013): 1-28.

[22] eDIL s.v. 1 bile or dil.ie/5885. See Michelle DiPietro, “Towards a cultural and chronological understanding of the Irish bile,” Ríocht na Midhe(2013): 1-28.

[22] eDIL s.v. 1 bile or dil.ie/5885. See Michelle DiPietro, “Towards a cultural and chronological understanding of the Irish bile,” Ríocht na Midhe(2013): 1-28.

[22] eDIL s.v. 1 bile or dil.ie/5885. See Michelle DiPietro, “Towards a cultural and chronological understanding of the Irish bile,” Ríocht na Midhe(2013): 1-28.

[22] eDIL s.v. 1 bile or dil.ie/5885. See Michelle DiPietro, “Towards a cultural and chronological understanding of the Irish bile,” Ríocht na Midhe(2013): 1-28.