When we study Renaissance literature why do we seldom talk or write about class? There have been numerous groundbreaking studies of race and gender in early modern writing but virtually nothing on class, apart from the pioneering work of Jean Howard and Christopher Warley.[1] The last sentence of the preface to Jonathan Dollimore and Alan Sinfield’s significant collection, Political Shakespeare, now over thirty years old, called on critics to establish an activist criticism which “register[ed] its commitment to the transformation of a social order which exploits people on grounds of race, gender and class.[2]

Clearly the hopes of cultural materialism have not borne fruit in this last area and, as the editor of one of the standard anthologies of writings on class admits, “Feminism has offered as great a challenge as any to the sovereignty of class in social theory, sociology, and history.”[3] Patrick Joyce’s point is not that feminism and class politics should be at odds, competing for dominance with class as an explanatory category. Rather, his argument is that in accepting a restricted focus of opposition to the status quo, critical discourses have sometimes obscured others and his comments serve as a warning not to separate out analyses of power structures as they work better together. The way forward is to think through structures of inequality, not to accept an agenda which simply celebrates diversity.[4]

The challenge is taken up by Katherine Landers in her excellent essay on ballads and gender/class issues in this volume.[5] However, it is a sadly acknowledged fact that whatever insights the “New Materialism” may have provided in terms of an analysis of objects and their human usage, class analysis—one of the central tenets of Marxist materialism—is certainly not one of them. As Jonathan Gil Harris acknowledges, “Studies of Renaissance objects have tended to offer little or no analysis of labor, class struggle, or relations of production.”[6] Materialism is not what it used to be.[7]

The question of how far the study of literature in terms of gender and race has transformed society remains open but surely there has been some positive effect given the number of books and articles written and graduates produced by literature departments; and teaching practices in higher education have certainly been altered, albeit not as radically as many would have liked.[8] The issue of class is far more problematic. Government statistics show that in 1992 17% of the British population were graduates, a figure that rose to 42% in 2017.[9] Official figures also show that, whatever benchmarking criteria are employed, widening participation in UK education appears to be working. However, if the figures are broken down further, the picture would appear to be rather more complicated and rather less positive.[10] Government statistical analysis suggests that attempts to increase the percentage of young adults in higher education have disproportionately favoured students from backgrounds already likely to attend higher education institutions, indicating that what has happened has been more of the same rather than a transformation of social access to higher education. Furthermore, not only are graduates now earning less than their counterparts from previous generations as the economy has stagnated, making higher education less advantageous as a means of social transformation than it used to be, but the gap between the haves and have-nots has widened.[11] Given this startling but sadly predictable context for our students, we surely need to talk more about class in the lecture hall and seminar room when we study literature, and direct our attention to matters of class in our research.

It is important to acknowledge that the notion of “class” is more complicated than ideas of rank and status, as it involves some sort of understanding of a particular social stratum to which people belong which distinguishes them from those above and below them in the social, political and economic order. Furthermore, members of a class need to feel some common interest and have a consciousness that can be shared by fellow economic and social actors, even if there are also important differences.[12] Being conscious of rank and status surely unites all societies: an understanding that class influences attitudes and behaviour is somewhat harder to prove. In this essay I will make the case that in the early modern period large groups of people saw that they had common goals, even if class consciousness as we understand it did not really occur until the transformations inaugurated by industrialisation. As Martine Segalen has argued “there can be no industrial development without a profound restructuring of social relations,” a truism which does not mean, of course, that class society cannot exist without industry.[13] There may not have been an obvious language for class relations and class consciousness, but Sir Thomas Smith’s De Republica Anglorum (written in the 1560s, published in 1583) has an elaborate taxonomy of social ranks, defining people as “sorts,” from those born to govern down to those who cannot rule “and yet they be not altogether neglected.” Smith’s social analysis surely suggests that thinking of socio-economic groups with common interests was not beyond the bounds of early modern thinkers.[14] Writers in Renaissance England certainly had the intellectual tools at their disposal to think about class: in particular, to think about why people remained at one social level and why others were able to change their status.[15]

Material Reality

Few people now believe that there was a series of dramatic social changes which can be identified, showing how a system of feudalism was transformed into a capitalist economy.[16] It may also be true that “broader class consciousness was inhibited for those below the level of the gentry by their lack of alternative conceptions of the social order,” as well as localism and relationships which demanded deference.[17] Even so, whatever model we might choose to define the social order and the hierarchies it relied on and precipitated, we need to recognise that society was structured in terms of a material reality; that material reality changed in the early modern period; and people understood that social changes were taking place. In Keith Wrightson’s words, where he borrows from William Cunningham and William James Ashley

Older economic institutions, relationships and expectations were dislocated. The economic structure of society was transformed and simplified around the three fundamental divisions of land, capital and labour in which “men arrange themselves according to the things they own and exchange”.[18]

Thinking about class matters has made a resurgence—in particular with the emergence of the problematic term “the white working-class” —and many acknowledge that contemporary society is based on class divisions.[19] The once common “bourgeoisification” argument, a belief that socio-economic progress meant that oppositional movements were becoming ever less effective as the working classes were bought off by the benefits of progress, is seldom heard now that we face times of severe and sustained economic crisis.[20] Class is recognised as a factor in major political events – in particular Brexit, the election of Donald Trump as US President and the spread of the coronavirus —even as commentators struggle to understand significant global technological changes which have transformed class consciousness and made once secure affiliations between class and politics far more problematic—and volatile—than they used to be.[21] Owen Jones’s bestselling Chavs (2011) showed how, in manipulating and then denigrating the aspirations, desires and achievements of the working-class, a poisonous and divisive class politics has been smuggled into the mainstream media masquerading as innocent, albeit scornful, comment.[22] Matters of class structure our reality, even as their significance is refused, ignored, obscured, or even forgotten.

The same can be said of early modern English society so, of course, writers write about class, even when they do not want to, which makes it odd that we now make so little of this vital issue which structures the nature of our lives, whoever we are, now as then. They were, of course, acutely conscious of existing within a society structured by class and having to adopt a class position. It is often pointed out that Shakespeare’s life was intimately bound up with money and anxieties about class and status, concerns which are often seen to diminish his literary celebrity, as though we should expect a universal genius to transcend the stuff of everyday life. Writing to combat this odd belief, Katherine Duncan-Jones argues that she does not think that “any Elizabethans … were what might now be called ‘nice’—liberal, unprejudiced, unselfish.” Rather,

For most men of talent and ambition in this period, even for those who, unlike Shakespeare, enjoyed the privileges of high birth, some degree of ruthlessness was a necessary survival skill… Three topics used to be traditionally taboo in polite society and in Shakespearean biography: social class, sex and money.[23]

In his recent study of Shakespeare’s money Robert Bearman shows how complicated, unstable and changeable his life, career, and wealth were.[24] Shakespeare’s father was a glover, a respectable trade, who enjoyed intermittent periods of prosperity but who fell on hard times during Shakespeare’s youth and was forced to sell off some of his property. Shakespeare worked as an actor and hack writer before becoming the shareholder of a company and accumulating enough wealth to buy significant property himself, enabling him to apply for a coat of arms. He clearly did well, but, if Bearman’s informed speculations are correct, he was by no means as wealthy as many assume and may well have struggled towards the end of his life.[25]

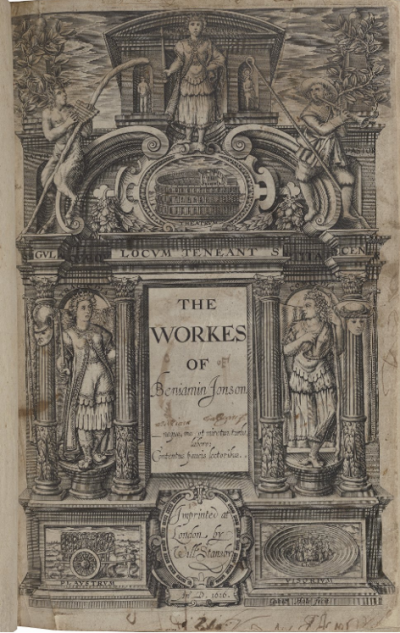

Shakespeare’s material existence, access to wealth, and giddy ride up and down the social hierarchy were hardly unusual for those outside the upper classes, a factor which surely increased awareness of social divisions and class status. Edmund Spenser, almost certainly from a similar background, achieved great wealth and status through acquiring an estate in Ireland and, as a result, the title of gentleman. Spenser’s riches came from his career in the civil service rather than his writing and his estate proved a precarious asset when the Munster Plantation was overrun during the Nine Years War and he was forced to flee, dying in London, according to Ben Jonson, “for lack of bread.” Jonson was probably not entirely accurate as the Spenser family retained the estates until the eighteenth century, but his offhand comment indicates the general belief in the instability of success as well as showing how common was the belief in the fickle nature of fortune.[26] The soldier–poet Thomas Churchyard toiled for years without conspicuous success until, like Spenser, he was awarded a pension by the queen towards the end of his life, presumably a reward for his longevity as much as his literary skill. His biographer wonders whether Churchyard sought “material prizes as monetary enrichment,” or “more intangible rewards” for his achievements, concluding that he would undoubtedly have accepted anything.[27] Writers such as Thomas Chettle and Robert Greene wrote an extraordinary number of works, amounting to thousands of pages as their long entries in the Short-Title Catalogue demonstrate, because, unlike Shakespeare and Spenser, they were not shareholders in a successful company and did not have another lucrative career which gave them the opportunity to accumulate property. They had to rely on their writing alone for income. John Donne was a successful man on the make enjoying significant patronage until his secret marriage ended his hopes of a court career and catapulted him into relative poverty. Having converted to the Church of England, his immediate elevation to senior positions, dean of St. Paul’s and royal chaplain, was probably based on his literary talents but, whatever the reason, was certainly an “irregularly … rapid promotion.”[28] Ben Jonson, like his collaborator and rival, Inigo Jones, was from a trade background, becoming important enough to have plays staged in the commercial theatre and at court and to have his works published in a folio the same year as the king published his.[29]

This list could go on: I have made no mention of Lyly, Middleton, Marlowe, Webster, and many others who could easily be considered in terms of shifting/unstable class positions. The point is that class was a significant and obvious factor in the lives of most writers, structuring their relationship to everyday reality. It is problematic to think about classes as sealed units which each had a particular mentality or ideology. E. P. Thompson opened up a whole series of possibilities in charting the making of the English working class, which showed the effects of social change on the lives and thinking of the majority of the English people.[30] It does not follow that we can therefore chart the histories of a series of classes and write about the rise of the middle class as a coherent group with their own ways of thinking, ideas, prejudices and tastes.[31] As Terry Eagleton sardonically—and rightly—pointed out recently, “If you open a history of Britain at random, it will tell you two things about the period you chance on: that it was a time of rapid change, and that the middle classes went on rising” (although recent developments would appear to suggest that the second of these historical features, once a seemingly inexorable process, has ended rather dramatically). However, we ignore the reality of the social relations under which writers existed at the cost of our own understanding of who they were.

It therefore follows that we cannot separate what writers wrote from their identities, one reason why it is so important to understand how people actually lived in the past.[32] English Renaissance literature, like the early modern lives of those who wrote it, is saturated with class consciousness. Most obviously writers endured the anxiousness generated by their insecure status: most were younger sons who had not inherited property and had to make use of their education and live by their wits, making them socially mobile (both upward and downward).[33] Their readerships were expanding, consisting of many from similar backgrounds: the process was even more pronounced in the public playhouses, which were patronised by many young apprentices, with equally dubious prospects.[34] It is hardly surprising that so many literary works focus, directly or indirectly, on the subject of class and social mobility.

New Class, New Drama

In Arden of Faversham, recently claimed for the Shakespeare canon, the murderous adulterers engage in a lovers’ tiff explicitly centred on class status.[35] As Alice and Mosby come closer to committing murder, they express doubts about their projected crime and desire to return to a tranquil existence. Alice laments her compromised status:

Ay, to my former happy life again;

From title of an odious strumpet’s name

To honest Arden’s wife – not Arden’s honest wife.

Ha, Mosby, ‘tis thou hast rifled me of that,

And made me sland’rous to all my kin.

Even in my forehead is thy name engraven,

A mean artificer, that low-born name.

I was bewitched; woe worth the hapless hour

And all the causes that enchanted me![36]

Alice describes her fall from grace in terms of her honest status as a loyal wife, but suggests that her shame is more dramatic because her partner in adultery is of a lower class status than she is. Her claim that she has been bewitched into acting against her best interests cleverly mirrors the more usual complaint of men led astray by unsuitable women and, understandably, provokes a reaction in Mosby.[37] He argues that he now sees her in her true colours, because “the rain hath beaten off thy gilt” so that “Thy worthless copper shows thee counterfeit” (8.100–101). He counters her claim that he is a witch with the assertion that she is a fake, a counterfeit coin now revealed for all to see, following on from her self-description as a woman who has her adultery emblazoned on her forehead. The verbal sparring is represented in terms of the reality of the lover’s lowly status finally coming to light. Mosby concludes his speech with the taunt that she is “a copesmate for thy hinds,” a contemptuous insult which casts Alice as someone best suited for an affair with a servant, because he is “too good to be [her] favourite” (8.104–105). Alice claims that he has bewitched her, undermining her good sense and compromising her status as a respectable married lady; Mosby argues that he is the one who has been taken in, imagining that she is a valuable asset when in fact she is nothing more than a loose woman who chases after her servants.

The exchange is replete with dramatic irony: far from vindicating either, what the audience understands is that both are greedy, unscrupulous and self-interestedly aspirational criminals, prepared to stop at nothing to satisfy their base desires and fuel their petty ambitions. Alice has acted as a social climber in marrying a wealthy man she does not love; Mosby has similar ambitions in planning to dispose of Arden and to marry his affluent widow. Their reconciliation is also cast in terms of anxieties of class status. When Alice claims that she will not trouble him anymore, Mosby responds:

Oh no, I am a base artificer,

My wings are feathered for a lowly flight.

Mosby? Fie, no! not for a thousand pound.

Make love to you? Why, ‘tis unpardonable;

We beggars must not breathe where gentles are (8.135–39).

In the context of the play—a murder for gain during the time after the dissolution of the monasteries when the Reformation provided immense opportunities for the personal enrichment of those able to grab land—these lines add further levels of irony.[38] As the plot makes clear, following the historical record in Holinshed’s Chronicles, this was exactly how the hard-headed Arden acquired his wealth. In the opening scene when he had learned of Mosby’s approaches to his already interested wife, Arden had asserted his rights as a husband, and as a man of status:

I am by birth a gentleman of blood,

And that injurious ribald that attempts

To violate my dear wife’s chastity—

For dear I hold her love, as dear as heaven—

Shall on the bed which he thinks to defile

See his dissevered joints and sinews torn,

Whilst on the planchers [floorboards] pants his weary body,

Smeared in the channels of his lustful blood (1.36–43).

Arden’s bloodthirsty desire for revenge for a crime which has not yet taken place, along with his professed love for his loyal wife, demonstrates his insecure status and the need for him to perform his role as a gentleman, imagining an ancient status through an unspecified bloodline, whereas in reality he was an arriviste, who, here, represents himself as a petty tyrant.[39] Arden’s assertion of his power to torture and kill any rival is a prefiguration of his own grisly death at the hands of four murderers. Alice is indeed a tarnished coin passed between two men of differing status who see her as a means to an end. Her character has to be seen in terms of both class and gender.[40]

Mosby’s profession of hurt innocence is as vulgar as Arden’s bragging assumption of his lofty status. Indeed, as Alice and Mosby are reconciled and move ever closer to committing a capital crime, it is not clear to the audience how sincere they have been in their quarrel or whether, like Arden, they are playing roles in order to get what they think they want. Mosby’s profession of principled and hurt innocence is countered by Alice’s performance of womanly supplication:

Sweet Mosby is as gentle as a king,

And I too blind to judge him otherwise.

Flowers do sometimes spring in fallow lands,

Weeds in gardens, roses grow on thorns;

So whatso’er my Mosby’s father was,

Himself is valued gentle by his worth (8.140–45).

Alice’s lines cunningly mix the language of tender love and the language of class. Furthermore, they intertwine two contrasting notions of class identity. The opening line casts Mosby as a gentle king, well-behaved and regal with an ancient bloodline, a pointed contrast to the brutal monarch in command of the torture chamber which Arden claims he is. As she claims that she is only now seeing the truth, countering Mosby’s statement that he had finally seen her for the counterfeit coin she really was, Alice flatters Mosby’s belief in his own self-sufficiency that his rise to higher status was entirely due to his own merits. Her strategy succeeds: even though Mosby recognises that she may not be entirely sincere (“how you women can insinuate, / And clear a trespass with your sweet-set tongue” (lines 146–47)), he ends the quarrel and promises to resume their relationship.

Arden of Faversham details the crime of petty treason, the murder of the head of the household (men who killed their wives were tried for murder; women who killed their husbands, petty treason, a crime against the state).[41] As such, it is a “domestic tragedy.”[42] Yet the audience is always aware that the play also works as a complicated allegory of class relations in the wake of Henry VIII’s decision to break with the Catholic Church. Arden’s representation of himself as a powerful monarch surely reminded at least some of the audience that his rise to the status of gentleman was made possible by the actions of a king who was quite prepared to torture and execute any opposition, making the crime he suffers strangely appropriate. The social revolution inaugurated by the dissolution of the monasteries made possible Arden’s rise, but also those of his nemeses, Alice and Mosby.[43] The play points to a moral, as all the villains pay for their crimes, but it is not a straightforward one. There is no obvious ethical centre, no undivided authority in this particular representation of status conscious, class-riven, post-Reformation England. Rather, there is an acute awareness that concepts of right and wrong were inevitable casualties in a country where the old order had crumbled and a new one was yet to be established. As a consequence, it was every man and woman for themselves, as the story of Arden demonstrates.

Class, Work, and Holiday

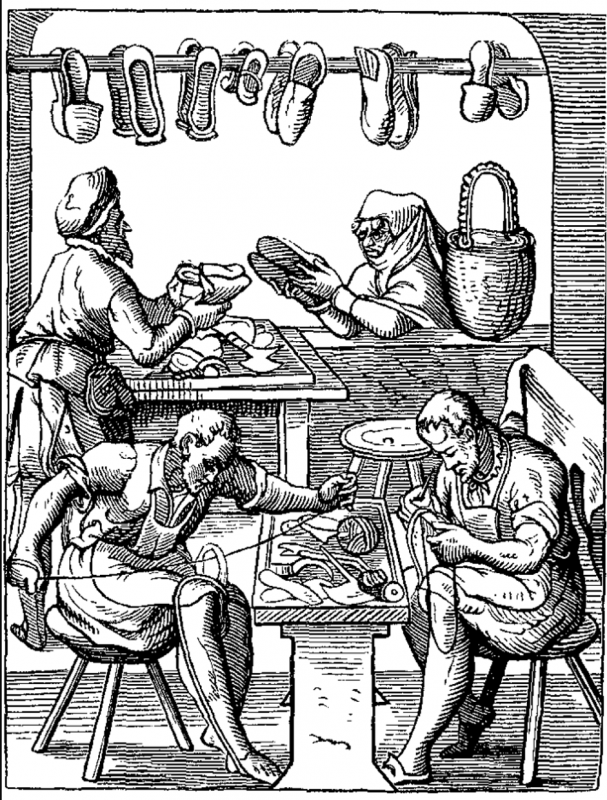

A more positive representation of class relations is provided in Thomas Dekker’s The Shoemaker’s Holiday, performed about a decade after Arden of Faversham in 1599.[44] The play shows the shoemakers enjoying their work, which is as much sociable leisure as hard labour. Moreover, their profession, one of the most powerful and successful of the London trade guilds, is buoyant enough to be able to absorb and celebrate foreign workers who can join their guild without problems.[45] The audience would have known that in the world outside the playhouse work was rarely as straightforward or as pleasurable. The play is framed as a fantasy, rather like the popular images of the “poor man’s heaven,” the “Land of Cockaigne,” which entails a life without work where wine is freely available, fruit drops into the hands of intoxicated, supine figures, and roast pigs with carving knives in their sides run around crying, “Eat me! Eat me!.”[46]

The play ends with the king attending a feast held in Simon Eyre’s honour, but the last lines, “When all our sports and banquetings are done, / Wars must right wrongs which Frenchmen have begun,” are a pointed reminder that in the real world many Londoners will have to endure the fate of Ralph, who returns from his conscripted service with a wooden leg, if they return to the capital at all (21.193-4).

The play opens with a scene that transports the audience from their familiar world into one which gradually shades into fantasy. The audience witnesses an animated conversation which has started before the action begins. Sir Hugh Lacy, earl of Lincoln, and Sir Roger Oatley, the Lord Mayor of London, have been discussing dining arrangements, but once on stage they turn their attention to the projected marriage of Lacy’s nephew, Roland, and Oatley’s daughter, Rose. It is a match that neither wants to see take place and each adopts what they imagine are cunning tactics in order to prevent the union. When Lincoln raises the subject, observing in an affectedly casual manner, “I hear my cousin Lacy / Is much affected to your daughter Rose” (1.5–6), Oatley turns what might be thought of as welcome news into something far more negative, setting the agenda for the dialogue that follows: “and she loves him so well / That I mislike her boldness in the chase” (lines 8–9). Lincoln’s “much affected” has become an unseemly boldness, a good example of paradiastole, rhetorical redescription which transforms the nature of the comment into its opposite.[47] In blaming his daughter for her behaviour, Oatley is attempting to generate further opposition to the match. When Lincoln provides him with a cue about Oatley’s apparent reluctance to see the names joined, designed to emphasise the gap in social status and pedigree between the families and so intimidate the Lord Mayor, Oatley responds:

Too mean is my poor girl for his high birth.

Poor citizens must not with courtiers wed,

Who will in silks and gay apparel spend

More in one year than I am worth by far.

Therefore your honour need not doubt my girl (11–16).

Oatley’s short speech begins with what appears to be due deference, but, like Mosby’s sarcastic representation of his humble status to Alice, his words are laced with class-based hostility. Oatley is defending the status and character of the London citizens, a self-sufficient class who can look after themselves, unlike the ridiculously profligate aristocracy who fritter away their money on ridiculous ephemera, echoing the familiar conflict between old and new money so frequently represented on the stage in this period.[48] The last line praises the character of his daughter, but it is ambiguous. Does he mean that she will be true in her suit because London citizens are steadfast and reliable? Or that she is of good character and, therefore, will eventually realise that it is not in her interests to be married to a feckless upper-class twit?

Take heed, my lord, advise you what you do.

A verier unthrift lives not in the world

Than is my cousin; for, I’ll tell you what,

‘Tis now almost a year since he requested

To travel countries for his experience.

I furnished him with coin, bills of exchange,

Letters of credit, men to wait on him,

Solicited my friends in Italy

Well to respect him. But to see the end:

Scant had he journeyed through half Germany

But all his coin was spent, his men cast off,

His bills embezzled, and my jolly coz,

Ashamed to show his bankrupt presence here,

Became a shoemaker in Wittenberg –

A goodly science for a gentleman

Of such descent! (16–31).

The speech is carefully designed to cause maximum irritation and panic for Oatley. The opening line is a reprimand, reminding the Lord Mayor that he is talking to a social superior and so needs to mind how he speaks, even if the second line suggests that he is merely advising him about his wayward nephew. He soon moves to a more intimately conspiratorial style, confiding his knowledge about Roland to someone who needs to understand what his nephew is really like. This manoeuvre then provides a guarantee that the details that follow are all accurate. According to Lincoln, Roland expressed the desire to undertake a grand tour, a venture that only aristocrats could possibly afford, and which was invariably a means of marking the transition into responsible adulthood by providing the young man with one last opportunity to sow his wild oats before settling down, as well as acquiring useful cultural and political capital.[49] Lincoln forcefully rams his point home by detailing all the forms of financial support the young man has been provided with and abused: coin, bills of exchange, letters of credit, servants, and the good will of influential friends. The list—indeed the act of making a list—mimics the professional concerns of the merchant class, patronising Oatley in the process, as he realises.[50] And the bankruptcy of Roland forces him to enter the class of apprentice labourers as a shoemaker, a descent down the social ladder which is anathema to the wealthy Lord Mayor, a position famous in legend, as the play recounts, for having more than its fair share of spectacularly successful social climbers.[51] There may be a further joke in the selection of Wittenberg, the location for the inauguration of the Reformation when Luther nailed his Ninety-five Theses to the church door on 31 October 1517, and, if Hamlet was staged in anything like its eventual form before the first performance of The Shoemaker’s Holiday at the Rose Theatre in autumn 1599, perhaps a sly reference to another young dissolute aristocrat who came to a bad end.[52]

The earl’s speech works at a meta-dramatic level as well: when he concludes that Lacy should really find “some honest citizen / To wed [his] daughter to” (lines 36–37), the audience, which probably contained many apprentices and craftsmen, would already have recognised the snobbish hostility of both men to their social class which sets up the plot whereby Ralph finds both love and redemption as a shoemaker.[53] Oatley acknowledges that Roland might well do better now that he has an honest trade, but his aside to the audience, “And yet I scorn to call him son-in-law” (line 44), positions him nearer to the earl than them.

The earl’s speech seems not to work as Oatley sees through his transparent disguise, as, of course, the audience would have done too: “Well, fox, I understand your subtlety” (line 39). But the joke is also on him as he is playing exactly the same game. In the end not only does Lincoln’s cunning trick to have Roland made chief colonel of the companies mustered in and around London fail, but the couple are united against all odds. In a time when most marriages needed to have some element of parental support, playgoers would have known that this was a significantly implausible fantasy of the triumph of love over class barriers.[54]

Paying attention to the class references in The Shoemaker’s Holiday emphasises the nature of the play as a fantasy. Throughout, the audience is aware of its fictive status, realising that what we witness on stage rarely happens in life. Dekker’s play is much more like Shakespeare’s romantic comedies than the satirical comedies of humours which had first appeared the previous year when Jonson’s Every Man in His Humour had been staged at the Curtain Theatre.

In the “Wars of the Theatres,” The Shoemaker’s Holiday looks like a play designed to appeal to an audience who might also enjoy As You Like It, probably also staged in 1599 as well as Henry V, another “at war” play which was written with Essex’s impending Irish campaign in mind.[55] Furthermore, Flavius’s pointed rhetorical question to the commoners celebrating the triumphs of Julius Caesar, “Is this a holiday?” at the start of Julius Caesar, one of whom is a cobbler, looks as if it were written with a knowledge of Dekker’s play, reminding the audience that the Globe trumped the Rose.[56]

Common Land and the Acquisitive Society

Class references played a significant role in establishing the structure of drama in Elizabethan and Jacobean England, as well as the nature of individual plays. Many works satirised the acquisitive society which was thought to have developed after the accession of James I, perhaps even competing with each other to see how far they could go. Certainly, the usury play, attacking the selfish accumulation of wealth at the expense of more honest citizens, became a staple genre in Jacobean England.[57] A relatively late example of the usurer figure appears in Philip Massinger’s A New Way to Pay Old Debts (c. 1621/2–1625, published 1633).

Few stage villains have enjoyed exploiting the poor and oppressed with as much gusto as Sir Giles Overreach. He explains his methods of exploitation to his pupil, Jack Marall:

I’ll therefore buy some cottage near his manor,

Which done, I’ll make my men break ope his fences;

Ride o’er his standing corn, and in the night

Set fire on his barns; or break his cattle’s legs.

These trespasses draw on suits, and suits expenses,

Which I can spare, but will soon beggar him.

When I have harried him thus two, or three year,

Though he sue in forma pauperis, in spite

Of all his thrift, and care he’ll grow behind-hand.[58]

Sir Giles’s professed tactics are a mixture of sharp but legitimate practice (buying properties bordering the victim’s land); illegal operations (destroying fences, burning barns, and mutilating cattle); and, to complete the process, legal bullying, knowing that he has deeper pockets than any opponent (in forma pauperis meant being too impoverished to pay legal fees). Enclosure—its extent and effectiveness in improving yields—is a matter of controversy among economic historians. What is clear is that the ruthless ambition of landowners like Sir Giles enabled them to extinguish common rights to the use of “fallow arable fields” and “common pasture.” Feelings of injustice and resentment at the destruction of ancient practices proliferated, often leading to riots in times of hardship, and were a common feature of the reality, and perception of the reality, of the economic conditions of pre-civil war England.[59]

A New Way to Pay Old Debts demonstrates that feelings of class conflict and economic grievance were not confined to the capital. This should not surprise us: after all, given the net migration of people to the capital, many would have chosen or been forced to leave the country as economic migrants. As Steve Rappaport points out,

Given the very high level of mortality in early modern London it is not surprising that the increase in its population was due entirely to the migration of people to the capital from towns, villages, hamlets, and farms throughout the realm where the birth rate was higher than the death rate, immigrants who represented much of the natural increase in the population elsewhere in England.[60]

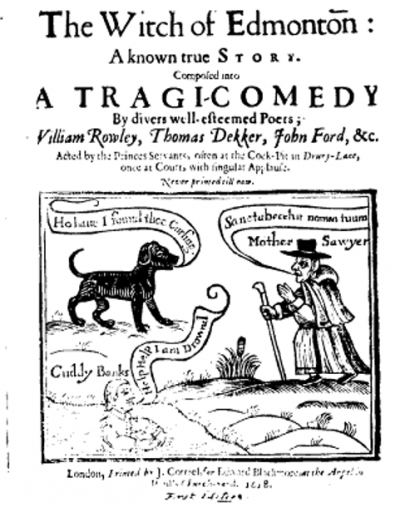

It should also not surprise us that Massinger’s play shows that the criminal practices of Sir Giles bear a striking resemblance to those levelled against witches, who were invariably accused of harming livestock and destroying crops. In her opening speech in Thomas Dekker, John Ford and William Rowley’s The Witch of Edmonton, which is almost exactly contemporary with A New Way to Pay Old Debts as it was first performed in 1621, Mother Sawyer laments that because she is “poor, deformed and ignorant” it is thought that her “bad tongue … / Forspeaks their cattle, doth bewitch their corn.”[61] Accusations of witchcraft were often rooted in economically deprived areas where there was competition for scarce resources: given that the majority of accusations were made against women, we have a further reminder that questions of class and gender should not be prised apart.[62]

The overarching point is that the stage was used to represent class conflict and class-based resentment and anxieties, exactly as we might expect given the social composition of theatregoers, many of whom were young, insecure, aspirational economic migrants and so would have experienced the social issues of the city or the country.

Court Poetry, Provincial Society, and Colonial Possession

Issues of class were not confined to drama but were the stuff of poetry too, especially work written by writers outside the metropolis who appeared to resent what they thought was the excessive influence of the court. One of these, I suspect, was the dominant poet of the 1590s, Edmund Spenser, writing from the most significant English colony established in Elizabeth’s reign, the Munster Plantation in Ireland.[63] Just as we cannot think about class without considering gender (and vice versa) we should also acknowledge that we cannot sever class politics from colonial expansion and occupation.

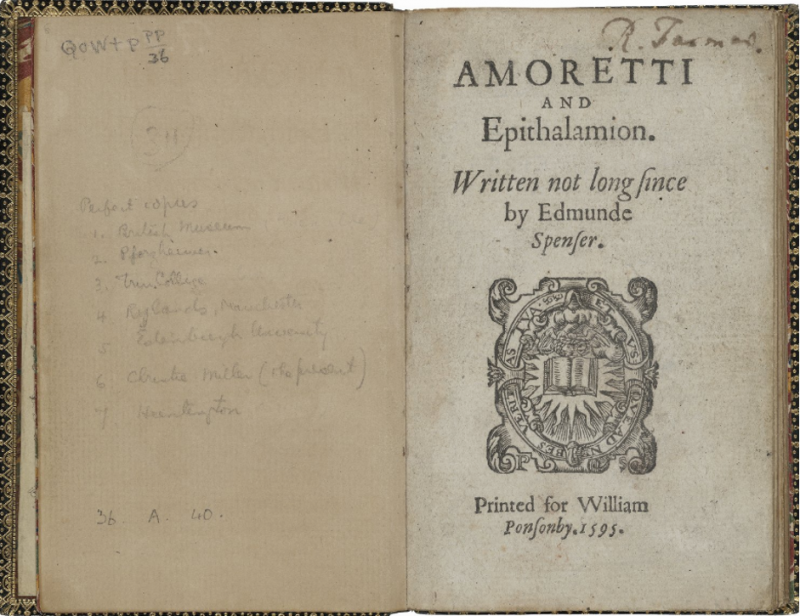

Spenser’s one sonnet sequence, the Amoretti, was designed as a celebration of Spenser’s marriage, a new departure in the recently established genre, which, following Sidney’s Astrophil and Stella, first published in 1591, had charted adulterous love or unrequited passion.[64] The Amoretti tell the story of Spenser’s courtship of Elizabeth Boyle, his second wife, the sequence culminating in another new form of English poem, the marriage hymn, the Epithalamion, as no one before had combined “the roles of bridegroom and poet–speaker.”[65] As Kenneth J. Larsen has demonstrated, “The eighty-nine sonnets of the Amoretti, as numbered in the 1595 octavo edition, were written to correspond with consecutive dates, beginning on Wednesday 23 January 1594 and running, with one interval, through to Friday 17 May 1594: they correspond with the daily and sequential order of scriptural readings that are prescribed for those dates by the liturgical calendar of the Church of England.”[66] Spenser narrates the course of his courtship and marriage of Elizabeth in terms of the prescribed Bible readings used by the established church, a token of his allegiance to that church, as well as a manifestation of the establishment of English culture in Ireland, one that proved all too fragile. Most importantly, he places his own identity as a poet at the centre of the poetic sequence.

The volume shows that, for Spenser, the colonists on the Munster Plantation believed that they had established a civilised order in Ireland that could rival and even supersede the tired culture of the court. The sequence, therefore, charts a significant shift in class culture as the aspirational literature of the colonists seeks to replace the language of court culture, locating the true focus of Englishness in the margins not the centre, where the hard-pressed colonists protect the lives and identities of those secure in the metropolis, a familiar, class-inflected colonial myth.[67] Spenser appropriates the language of the courtly lyric—in the main that of Sidney’s sequence—in order to praise his bride-to-be, translating the tropes of courtiers to a conspicuously provincial, commercial scene:

Ye tradefull Merchants that with weary toyle,

do seeke most pretious things to make your gain:

and both the Indias of their treasures spoile,

what needeth you to seeke so farre in vaine?

For loe my loue doth in her selfe containe

all this worlds riches that may farre be found;

if Saphyres, loe her eies be Saphyres plaine,

if Rubies, loe hir lips be Rubies found;

If Pearles, hir teeth be pearles both pure and round;

if Yuorie, her forhead yuory weene;

if Gold, her locks are finest gold on ground;

if siluer, her faire hands are siluer sheene,

But that which fairest is, but few behold,

her mind adornd with vertues manifold.[68]

Elizabeth is as beautiful as any courtly lady, and Spenser’s sonnet may well have Astrophil’s ornate description of Stella’s face in mind, transposing the elaborate ironies of that poem to a new, middle-class setting and a different series of literary co-ordinates. Sidney’s poem reads:

Queen Virtue’s court, which some call Stella’s face,

Prepar’d by Nature’s choicest furniture,

Hath his front built of alabaster pure;

Gold in the covering of that stately place.

The door by which sometimes comes forth her Grace

Red porphyr is, which lock of pearl makes sure,

Whose porches rich (which name of cheeks endure)

Marble mix’d red and white do interlace.

The windows now through which this heav’nly guest

Looks o’er the world, and can find nothing such,

Which dare claim from those lights the name of best,

Of touch they are that without touch doth touch,

Which Cupid’s self from Beauty’s mine did draw:

Of touch they are, and poor I am their straw.[69]

Sidney’s poem asserts that his lady has all these marvellous possessions as part of her substance; in pointed contrast, Spenser claims that his is better than these things, establishing a distance between her (middle-class, trade) virtues and the riches that the merchants bring back from far-flung lands, most of which, presumably, end up at court and in the possession of courtiers. Furthermore, Spenser’s love is witnessed by merchants, not courtiers, and her commodified body serves to revitalise them, the real substance of society, not those at court who imagine that their actions run the country.[70] The opening quatrain claims that foreign exploration is probably a waste of time, as more profit will be gained, financially and spiritually, by planting colonies within the “British Isles” and securing England’s possessions closer to home, a development that would involve the strengthening and proliferation of nearby plantations, not the spectacular voyages of explorers and empire builders which invariably disappointed investors.[71] Of course, in doing so, Spenser is performing a cunning sleight of hand, writing as though Ireland were not a colony but part of the queen’s legitimate possessions and that in marrying Elizabeth and establishing their home in Ireland, they are effecting domestic harmony and shoring up the realm, making them better citizens than their more celebrated and exalted counterparts who grab overseas possessions.[72] In domesticating the colonial context of his wedding Spenser is disguising the origins of his own wealth and obscuring his role as a man on the make.[73]

The description is repeated in the tenth stanza of the Epithalamion, when the poet-narrator asks, “Tell me ye merchants daughters did ye see / So fayre a creature in your towne before” (l. 168–69), followed by a similar depiction of Elizabeth in terms of a blazon invariably applied to court beauties.[74] Spenser reminds his readers that his bride has a radiance that puts them to shame, marking the couple out as both part of the community and yet also separate from it, a poet and his wife who simultaneously represent and transcend the virtues of the merchant community in the south of Ireland.

Hack Writing in Old Grub Street

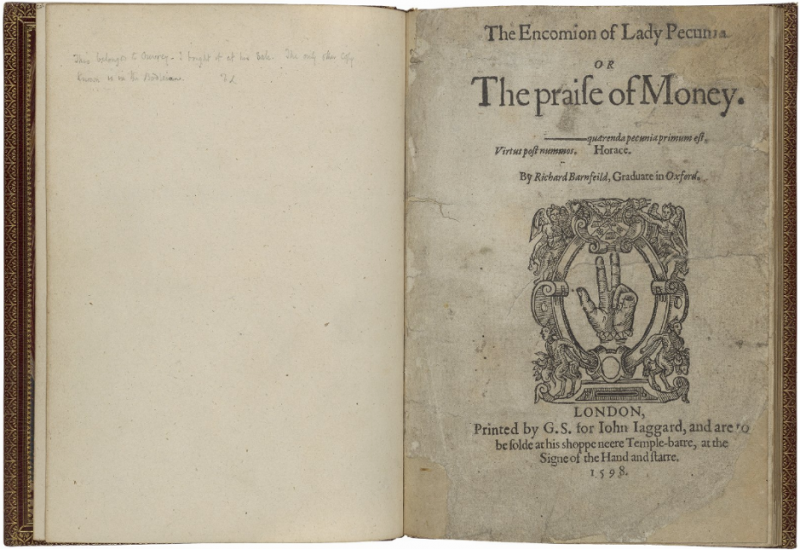

Spenser’s sonnet can be read as part of a concerted attempt to place himself as the next national poet after Sidney, which probably explains why his poem lamenting the premature death of Sidney appears so late and coincides with Spenser’s rise as a poet rather than appearing immediately after the funeral.[75] For many poets lacking secure patronage the economic reality of their working lives was far more harsh than it was for Spenser and the treadmill of producing work for profit, or in the hope of securing a wealthy patron, was more debilitating and penurious than for the impoverished hack writers struggling in George Gissing’s New Grub Street. Writing, whatever its practitioners might think, was very much a trade for anyone outside the court around 1600, with authors working hand-in-hand with their social equals, printers, publishers and booksellers.[76] Richard Barnfield’s The Prayse of Lady Pecunia, published as part of Barnfield’s last short volume in 1598, fits into a long tradition of poetic complaints about money. Barnfield refers to Erasmus’s Praise of Folly, a model for his representation of Lady Pecunia, the personification of money, but the poem can be related to the ploughman tradition lamenting that the once stable values on which society was founded have been corrupted by the lure of monetary gain.[77]

As Barnfield’s editor, George Klawitter suggests, it is hard to tell “whether Barnfield is commenting on the lack of money in his own pocket or commenting more generally on the lack of patrons for all poets,” but the scarcity of dedications in Barnfield’s books suggest that he is writing from personal experience.[78] Barnfield’s narrator states that “The Meane is best, and that I meane to keepe,” the quibbling line suggesting that money is not bad in itself, only when it is responsible for malign effects.[79] Like Massinger and other dramatists, his persona argues that money has become the dominant force in contemporary society and subsumed everything else:

She is the Soveraigne Queene, of all Delights:

For her the Lawyer pleades; the Souldier fights.

For her, the Merchant venters on the Seas:

For her, the Scholler studdies at his Booke:

For her, the Usurer (with greater ease)

For sillie fishes, layes a silver hooke:

For her, the Townsman leaves the Countrey Village:

For her, the Plowman gives himselfe to Tillage.

For her, the Gentleman doeth raise his rents:

For her, the Servingman attends his maister:

For her, the curious head new toyes invents:

For her, to Sores, the Surgeon layes his plaister.

In fine for her, each man in his Vocation,

Applies himselfe, in everie sev’rall Nation.What can thy hart desire, but thou mayst have it,

If thou hast readie money to disburse?

Then thanke thy Fortune, that so freely gave it;

For of all friends, the surest is thy purse.

Friends may prove false, and leave thee in thy need;

But still thy Purse will bee thy friend indeed (95–114).

Barnfield surely has one of Erasmus’s most celebrated adages in mind here, “Friends hold all things in common,” in showing how Lady Pecunia has become everyone’s new best friend and so destroyed all previous relationships of friendly equality.[80] Every productive activity and every social relation has been undermined by the advent of monetary relations. As in other conservative critical traditions Barnfield looks back to a time of order, justice, and a proper understanding of a balanced and harmonious society.[81] Barnfield’s examples of professions are traditional and look back to the late Middle Ages: lawyers, soldiers, merchants, scholars, ploughmen, surgeons, and usurers. His most likely sources are the fourteenth-century literature of Chaucer and Langland, both of whom were published in substantial editions in the sixteenth century, and the style of this passage bears more than a passing resemblance to the ending of Troilus and Criseyde.[82]

Barnfield is arguing that society is out of joint. Even though he praises Elizabeth as a queen who has restored the proper value of money, purified a debased and counterfeited coinage (l. 204–10) and so rebalanced social relations, he makes it clear that all is not yet right:

No flocke of sheepe, but some are still infected:

No peece of Lawne so pure, but hath some fret:

All buildings are not strong, that are erected:

All Plants prove not, that in good ground are set:

Some tares are sowne, amongst the choicest seed:

No garden can be cleansd of every Weede (lines 211-6).

The stanza might be read alongside the comments about coinage in Arden of Faversham. Again, the analogy represents society in a very traditional light – this time explicitly employing the rural idiom of the ploughman, gardener and shepherd. His real fear, one articulated throughout the early modern period, is that vertical and horizontal social relations have been obliterated by money so that no one understands any longer where they are or where they should be.

As with drama, many more examples could be cited (Nicholas Breton, Michael Drayton, George Gascoigne, John Taylor, to name only a few), and I have made no mention at all of prose. Writers in Renaissance England were acutely aware of social status and class divisions, at the upper and lower ends of the social scale. Raymond Williams is right to point out that the growing importance of the idea of class “relates to the increasing consciousness that social position is made rather than merely inherited.”[83] But assuming that people were indifferent to such issues because they are a specifically modern phenomenon, or that thinking about class, rank and status was the preserve of a tiny minority, distorts our ability to read earlier literature, and, more seriously, our understanding of the relation of the present to the past. For too long readers have laboured under the misapprehension that “class” is scarcely relevant to an understanding of literature before the middle of the seventeenth century. Even histories of the Civil War avoid or dismiss explanations of the conflict as class-based, concentrating on local, religious and national influences.[84] The assumption now appears to be that class either played no role in the public imagination or, perhaps, did not exist at all before the advent of industrial society. Commentators and critics write as if class explains everything or nothing, whereas the truth is surely more complicated and messy. The time has surely come to acknowledge that a history of literature with the class taken out risks not being history at all.

Bibliography:

Akala, Natives: Race and Class in the Ruins of Empire. London: Two Roads, 2018.

Anon., Arden of Faversham, ed. Martin White. London: A. C. Black, 1982.

Barnfield, Richard. The Complete Poems, ed. George Klawitter. Selinsgrove: Susquehanna University Press, 1990

Bearman, Robert. Shakespeare’s Money: How much did he make and what did this mean? New York: Oxford University Press, 2016.

Bednarz, James P. Shakespeare & The Poets’ War. New York: Columbia University Press, 2001

Beetham, David. “Reformism and the ‘Bourgeoisification’ of the Labour Movement,” in Socialism and the Intelligentsia 1880–1914, ed. Carl Levy. New York: Routledge, 1987. 106–34.

Belsey, Catherine. “Alice Arden’s Crime,” in The Subject of Tragedy: Identity and Difference in Renaissance Drama. London: Methuen, 1985. 129–48.

Black, Jeremy. The British Abroad: The Grand Tour In The Eighteenth Century (Gloucester: Sutton, 1992).

Bucholz, Robert O. and Joseph P. Ward, London: A Social and Cultural History, 1550-1750. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Butler, Martin. “Appendix 2: Shakespeare’s Unprivileged Playgoers, 1576–1642,” in Theatre and Crisis, 1632–1642. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1984. 293–306.

Chaucer, Geoffrey. “Troilus and Criseyde,” in The Riverside Chaucer, ed. Larry D. Benson et al. New York: Oxford University Press, 1987. 471-586.

Coleman, D. C. The Economy of England, 1450-1750. New York: Oxford University Press, 1977)

Connolly, William E. “The ‘New Materialism’ and the Fragility of Things,” in Millennium: Journal of International Studies 41.1 (2013): 399-412.

Cressy, David. Birth, Marriage & Death: Ritual, Religion, and the Life-Cycle in Tudor and Stuart England. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), 298–315.

Dasenbrock, Reed Way. ‘The Petrarchan Context of Spenser’s Amoretti,’ PMLA 100 (1985): 38–50.

Dekker, Thomas. The Shoemaker’s Holiday, ed. Anthony Parr. London: A. C. Black, 1990.

Dekker, Thomas, John Ford, and William Rowley. “The Witch of Edmonton” in Three Jacobean Witchcraft Plays, ed. Peter Corbin and Douglas Sedge. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1986.

Dobranski, Stephen B. Readers and Authorship in Early Modern England. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

Dollimore, Jonathan and Alan Sinfield. “Foreword,” in Political Shakespeare: Essays in Cultural Materialism. Ed. Jonathan Dollimore and Alan Sinfield. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1985. vi-viii.

Donaldson, Ian. Ben Jonson: A Life. New York: Oxford University Press, 2011.

Donne, John. The Oxford Edition of the Sermons of John Donne: Volume 1, Sermons Preached at the Jacobean Courts, 1615–1619, ed. Peter McCullough. New York: Oxford University Press, 2015.

Duncan-Jones, Katherine. Ungentle Shakespeare: Scenes from his Life. London: Thomson Learning, 2000.

Dunlop, Alexander. “Calendar Symbolism in the Amoretti,” Notes & Queries 16 (1969): 24–26

Eden, Kathy. Friends Hold All Things in Common: Tradition, Intellectual Property, and the Adages of Erasmus. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001.

Elliott, Jack and Brett Greatley-Hirsch, “Arden of Faversham, Shakespearean Authorship and ‘The Print of Many,’” in The New Oxford Shakespeare Authorship Companion, eds. Gary Taylor and Gabriel Egan. New York: Oxford University Press, 2017. 139–81.

Elliott, Larry and Katie Allen. “UK Faces Return to Inequality of Thatcher Years, Says Report,” The Guardian, January 31, 2017. (https://www.theguardian.com/business/2017/jan/31/theresa-may-inequality-margaret-thatcher-resolution-foundation) (accessed 14 September 2018)

Findlen, Paula. Early Modern Things: Objects and their Histories, 1500-1800. New York: Routledge, 2013.

Evans, Maurice ed., Elizabethan Sonnets. London: Dent, 1977.

Federici, Sylvia. Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation. Brooklyn: Autonomedia, 2004.

Fraser, Duncan and Andrew Hadfield, eds., Gentry Life in Georgian Ireland: The Letters of Edmund Spencer (1711–1790). Oxford: Legenda, 2017.

Gest, David. The White Working Class: What Everyone Needs to Know. New York: Oxford University Press, 2018.

Gibbons, Brian. Jacobean City Comedy: A Study of Satiric Plays by Jonson, Marston and Middleton. London: Hart-Davies, 1968.

Greene, Thomas M. “Spenser and the Epithalamic Convention,” Comparative Literature 9 (1957): 215–28.

Grössinger, Christa. Picturing Women in Late Medieval and Renaissance Art. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1997.

Gurr, Andrew. The Shakespearean Stage, 1574–1642. New York: Cambridge University Press, 3rd edition, 1999

Hadfield, Andrew. Edmund Spenser: A Life. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012)

—–. “Foresters, Ploughmen and Shepherds: Versions of Tudor Pastoral,” in Mike Pincombe and Cathy Shrank, eds., The Oxford Handbook to Tudor Literature, 1485–1603. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009. 537–53.

—–. “Foreword: Why Does Literary Biography Matter?.” Shakespeare Quarterly 65 (2015): 371–78.

—–. “Lenten Stuff: Thomas Nashe and the Fiction of Travel,” The Yearbook of English Studies 41 (2011): 68–83.

—–. “War Poetry and Counsel in Early Modern Ireland,” in Elizabeth I and Ireland, ed. Valerie McGowan-Doyle and Brendan Kane. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014. 239–60.

Harris, Jonathan Gil. Untimely Matter in the Time of Shakespeare. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009.

Heal, Felicity. Reformation in Britain and Ireland. New York: Oxford University Press, 2003.

Helgerson, Richard. The Elizabethan Prodigals. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1976.

Hilton, Rodney. “Introduction” in The Transition from Feudalism to Capitalism. Ed. Rodney Hilton. London: New Left Books, 1976.

Hoskins, W. G. The Age of Plunder: King Henry’s England 1500–1547. Harlow: Longman, 1976.

Howard, Jean E. The Stage and Social Struggle in Early Modern England. New York: Routledge, 1994.

James, Lawrence. The Middle Class: A History. London: Little Brown, 2006.

Johnson, William C. ‘Spenser’s Amoretti and the Art of the Liturgy,’ Studies in English Literature, 1500–1900 14 (1974): 47–61.

Jones, Owen. Chavs: The Demonization of the Working Class. London: Verso, 2012.

Joyce, Patrick, ed. Class. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995.

Kastan, David Scott. “Workshop and/as Playhouse: Comedy and Commerce in The Shoemaker’s Holiday,” Studies in Philology 84 (1987): 324–37.

Keown, Michele. “Teaching Postcolonial Literature in an Elite University: An Edinburgh Lecturer’s Perspective,” Journal of Feminist Scholarship 7/8 (Fall 2014/Spring 2015): 102-109.

Kermode, Lloyd Edward ed., Three Renaissance Usury Plays. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2009.

Knapp, Jeffrey. An Empire Nowhere: England, America, and Literature from Utopia to The Tempest. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992

Knowles, James, ed. The Roaring Girl and Other City Comedies. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Lever, J. W. The Elizabethan Love Sonnet. London: Methuen, 1956.

Lucas, Scott. “Diggon Davie and Davy Dicar: Edmund Spenser, Thomas Churchyard, and the Poetics of Public Protest,” Spenser Studies 16 (2001): 151–65.

Mason, Paul. Post-Capitalism: A Guide to our Future. London: Allen Lane, 2016.

Massinger, Philip. A New Way to Pay Old Debts, ed. T. W. Craik. London: A. C. Black, 1964.

Mendelson, Sara and Patricia Crawford, Women in Early Modern England. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Montaño, John Patrick. The Roots of English Colonialism in Ireland. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

Morton, A. L. The English Utopia. London: Lawrence & Wishart, 1978.

Rappaport, Steve. Worlds Within Worlds: Structures of Life in Sixteenth-Century London. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1989.

Reddy, William L. “The Concept of Class,” in Social Orders & Social Class in Europe Since 1500: Studies in Social Stratification. ed. M. L. Bush (Harlow: Longman, 1992), 13–25.

Rhodes, Neil. Common: The Development of Literary Culture in Sixteenth-Century England. New York: Oxford University Press, 2018.

Riggs, David. The World of Christopher Marlowe. London: Faber, 2004.

Roberts, Penny. “Witchcraft and Magic,” in The European World, 1500-1800: An Introduction to Early Modern History, ed. Beat Kümin. New York: Routledge, 2009. 203–14.

Segalen, Martine. “The Family in the Industrial Revolution,” in A History of the Family, ed. André Burguière et. al., trans. Sarah Hanbury Tenison, 2 vols. (Cambridge: polity, 1996). II.377–415

Shakespeare, William. Julius Caesar, ed. David Daniell. London: Thomson, 1998.

Shapiro, James. 1599: A Year in the Life of William Shakespeare. London: Faber, 2005.

Sidney, Sir Philip. “Sonnet 9 from Astrophil and Stella,” in Elizabethan Sonnets, ed. Maurice Evans. London: Dent, 1977. 5.

Skinner, Quentin. Visions of Politics: Volume III, Hobbes and Civil Science. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

Smith, Sir Thomas. De Republica Anglorum: A Discourse on the Commonwealth of England, ed. L. Alston. Shannon: Irish University Press, 1972, rpt. of 1906.

Spenser, Edmund. Edmund Spenser’s Amoretti and Epithalamion: A Critical Edition, ed. Kenneth J. Larsen. Tempe: MRTS, 1997.

—–. The Yale Edition of the Shorter Poems of Edmund Spenser, ed. William A. Oram, et. al. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1989.

Sullivan, Ceri. The Rhetoric of Credit: Merchants in Early Modern Writing. Cranbury, NJ: Farleigh Dickinson University Press, 2002.

Thompson, E. P. The Making of the English Working Class. New York: Penguin, 1963.

Vickers, Nancy. ‘Diana Described: Scattered Woman and Scattered Rhyme,’ Critical Inquiry 8 (1981), 265-79.

Warley, Christopher. Reading Class Through Shakespeare, Donne, and Milton. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

—–. Sonnet Sequences and Social Distinction in Renaissance England. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

Weale, Sally and Richard Adams, “Gap between Graduate and Non-Graduate Wages ‘Shows Signs of Waning’,” The Guardian, August 17, 2016 (https://www.theguardian.com/education/2016/aug/18/gap-between-graduate-and-non-graduate-wages-shows-signs-of-waning) (accessed 14 September 2018)

Welsford, Enid. Spenser: Fowre Hymnes, Epithalamion: A Study of Edmund Spenser’s Doctrine of Love. Oxford: Blackwell, 1967.

Williams, Raymond. “Class,” in Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society. London: Fontana, 1976. 60–69

Wood, Andy. The Memory of the People: Custom and Popular Senses of the Past in Early Modern England. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

Woodcock, Matthew. Thomas Churchyard: Pen, Sword, & Ego. New York: Oxford University Press, 2016.

Worden, Blair. The English Civil Wars: 1640–1660. London: Phoenix, 2009.

Wrightson, Keith. Earthly Necessities: Economic Lives in Early Modern Britain. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000.

—–. English Society, 1580–1680. London: Hutchinson, 1982.